- Welcome

- Noir Zine

- Allan Guthrie

- Books

"...those who enjoy the darker side of the genre are in for some serious thrills with this..."

Laura Wilson, The Guardian

Published in the UK by Polygon (March 19th, '09) and in the US by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (Nov '09).

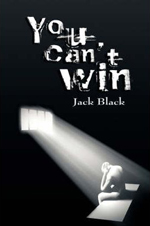

YOU CAN'T WIN

by Jack Black

reviewed by Matthew Loukes

When Dashiell Hammett first pulled crime from the posh flowerpots of upscale drawing rooms and tossed it into the alley where it belonged I wouldn’t be in the least bit surprised to have seen it hit Jack Black square in the face, in the act of pegging the place looking for a score. Black’s memoir of a criminal life full of hobo, hop and hopelessness, You Can’t Win, was published in 1926; around the same time as the explosion of what we might call modern American crime fiction, or noir. The timelines don’t quite match, of course, and I don’t want to set the scholars off, but it seems to me that it’s hardly fanciful to place You Can’t Win somewhere that looks back at a faded wanted poster of Jesse James while wondering who the man in front is; the one wearing a chalk-stripe suit and carrying a Tommy Gun.

If Noir has an underlying theme, and I don’t insist on it, it could be said to be about ruin and the literal meaning of the word disgrace. Protagonists tend to lose things, from jobs to liberty; from wives to life itself. It might be at the hand of a woman in a blue dress holding a blade or a granite-faced jailer pulling an anonymous lever; but the end result is the same. A fall from grace, one way or another, even if the original state wouldn’t end up in any good news stories. The start point is not the issue as much as the depth of the decline. Overlaying all this, of course, is a sense of dread that the end is not just inevitable but the direct result of a series of bad decisions. Jack Black knew this and the title itself is pure noir. You Can’t Win. Yeah, we know.

If Noir has an underlying theme, and I don’t insist on it, it could be said to be about ruin and the literal meaning of the word disgrace. Protagonists tend to lose things, from jobs to liberty; from wives to life itself. It might be at the hand of a woman in a blue dress holding a blade or a granite-faced jailer pulling an anonymous lever; but the end result is the same. A fall from grace, one way or another, even if the original state wouldn’t end up in any good news stories. The start point is not the issue as much as the depth of the decline. Overlaying all this, of course, is a sense of dread that the end is not just inevitable but the direct result of a series of bad decisions. Jack Black knew this and the title itself is pure noir. You Can’t Win. Yeah, we know.

Jack Black’s criminal activities covered most of the bases, from safe-cracking to armed robbery with a fair smattering of house-breaking and jeweller’s shops chucked in for good measure. His associates range from prostitutes to card sharps, stone killers to stoned opium addicts and a range of tramps, hobos and jailbirds that would have had Damon Runyan feverishly sharpening his pencil. In You Can’t Win each of the escapades are laid out like one long charge sheet with little by way of apology or regret (although I suspect the publishers of the times pushed some in here and there to give the work ‘moral value’) . These things happened, says Black, that’s the way it was. Sympathy is neither offered nor asked for except in some hilariously bleak depictions of plumb bad luck ruining a good scam.

This plain prose style has been used by all kinds of writers, from Charles Bukowski to Charles Willeford; noir fiction is full of it. One theory would say there’s no need for literary curlicues when the action is so rich, and richly dreadful. Also, and this is something that perhaps makes reading books in the 20th century different from what went before, is that readers have pictures in their heads to start with. We think we know what a bum jumping on a freight train looks like. A man eating a plate of thin soup in a hash house with a tired looking woman standing over him is, to us, a familiar image even if we’ve never actually seen it. And so is a murder, something most readers have no direct experience of at all. Black doesn’t bother too much with telling the audience about the way things look, he just puts it down. I for one was already there after the reading the dedication page. To “that dirty, disreputable, crippled beggar, ‘Sticks’ Sullivan who picked the buckshot out of my back – under the bridge – at Baraboo Wisconsin”.

Crime fiction, and noir in particular, has thrown up some memorable characters with names that in themselves speak of excitement, fear, sex and mystery. Who could see the names Moose Malloy or Velma Valento without wanting to find out more? Well, You Can’t Win has a stack of them. Salt Chunk Mary (who was “as right as April rain”) a tough female fence running a kind of soup-kitchen for low lives is among the most striking not least because of her handy way with a broken beer bottle. But you can also get off to The Sanctimonious Kid, Foot and a Half George, Soapy Smith, St Louis Frank and Gold Tooth. Add to this cast-list a collection of dumb and/or venal lawmen, some Chinese Opium dealers and a set piece scene of a convention of drifters and criminals drinking the night away and committing the odd murder. You Can’t Win has enough material for a shelf of noir titles on the strength of the names alone.

Crime fiction, and noir in particular, has thrown up some memorable characters with names that in themselves speak of excitement, fear, sex and mystery. Who could see the names Moose Malloy or Velma Valento without wanting to find out more? Well, You Can’t Win has a stack of them. Salt Chunk Mary (who was “as right as April rain”) a tough female fence running a kind of soup-kitchen for low lives is among the most striking not least because of her handy way with a broken beer bottle. But you can also get off to The Sanctimonious Kid, Foot and a Half George, Soapy Smith, St Louis Frank and Gold Tooth. Add to this cast-list a collection of dumb and/or venal lawmen, some Chinese Opium dealers and a set piece scene of a convention of drifters and criminals drinking the night away and committing the odd murder. You Can’t Win has enough material for a shelf of noir titles on the strength of the names alone.

It’s hard to forget that noir tends to feature women heavily and not always in a way that shows the author in a good light. Men are brought low, driven mad with desire, or left broken, beaten, behind bars and in the ground by dames, broads, vixens, minxes and high class pieces. Apart from the solid and sound Salt Chunk Mary (a feminist heroine of sorts), the women in You Can’t Win fit the pattern well enough, although Jack is keen to show that it’s the man’s fault, more often than not. Julia, a working woman, has a story “as old as man’s duplicity” and by and large the women get the same respect as everyone else. That is to say, everyone’s equal, and no judgements are made but keep a tight grip on your handbag, just in case. It’s another in a pile of things that make You Can’t Win like an encyclopaedia of the familiarly criminal, or the criminally familiar.

I remember seeing an old edition of one of the Raymond Chandler novels with a quote on it about how “no consideration of modern American literature ought, I think, to exclude him”. I’d say the same thing ought to be applied to Jack Black. I don’t much care if it’s crime or not, noir or blank verse, Jack Black’s eyes and ears merit him a place in the guide books. I’d accept that the reformist elements of the work, and the message to the reader that this life isn’t a good one push the book outside the framework of noir but I can’t believe that the things that happen in the book aren’t slap bang in the middle of the dark place where people do such terrible things to each other.

# # #

Copyright © Matthew Loukes, 2009

Read an extract from Matthew Loukes' Goose Flesh

MATTHEW LOUKES is 44, married for more than 10 years and lives in North London and is a graduate of the inaugural creative writing MA at Birkbeck. In 1998 he was shortlisted for the CWA/Sunday Times New Crime Writers award. His first novel Estrella Damn, featuring investigator Slim Gunter, was published by Soul Bay Press in 2008. Matthew’s second Slim Gunter novel, GOOSE FLESH, will be out in September 2009. Beyond crime fiction, his interests include cookery and tattooing.