- Welcome

- Noir Zine

- Allan Guthrie

- Books

"...those who enjoy the darker side of the genre are in for some serious thrills with this..."

Laura Wilson, The Guardian

Published in the UK by Polygon (March 19th, '09) and in the US by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (Nov '09).

William Campbell Gault: An Author From The Old School

An Author From The Old School

For This Writer, There’s No Mystery About What Sells

by David Laurence Wilson

This article first appeared in the Los Angeles Times, December 14, 1984, and has not been updated.The unpublished novel mentioned is Man Alone, which came out in 1995 from Gryphon Books. That same year, sadly, William Campbell Gault passed away.

Old is new and vice versa. Today the new mystery writers are imitating the old school, sending out apparitions of Bogart in period dress and slang. Critics and publicists alike hold up the names of Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett like lucky charms.

But it’s tough to be a hard-boiled detective writer. Just ask the chain-smoking William Campbell Gault, creator of the Brock Callahan series. Gault, 74, is coming on like the hottest kid in town.

"Death in Donegal Bay" (Walker: $12.95) is Gault’s third new Callahan mystery after nearly a 20-year absence from the field. During the layoff, while Gault wrote juvenile sports novels, his reputation as a detective writer grew. In the compendious "Twentieth Century Crime and Mystery Writers" published by St. Martin’s, he was hailed for his "keen observation, coherent plotting and fresh, direct writing." His work was called "undeservedly neglected." In 1976, Ross MacDonald dedicated his last book, "The Blue Hammer," to him, writing in his copy: "To Bill Gault, who knows that writing well is the best revenge."

Gault is a commercial writer. He has no qualms about that designation and is uncomfortable when the academics begin pontificating about the mystery genre, laying out superlatives about writers taking the field beyond its limits. "If you want to take the field beyond its limits go out and do it -- try to write some of the straight stuff. Don’t talk about sociological treatises and all that. If you want to write a sociological treatise write one. If you want to bat with the majors go up there, but don’t stay in the Texas League and say that you’re batting in the majors. You’re not.

Gault is a commercial writer. He has no qualms about that designation and is uncomfortable when the academics begin pontificating about the mystery genre, laying out superlatives about writers taking the field beyond its limits. "If you want to take the field beyond its limits go out and do it -- try to write some of the straight stuff. Don’t talk about sociological treatises and all that. If you want to write a sociological treatise write one. If you want to bat with the majors go up there, but don’t stay in the Texas League and say that you’re batting in the majors. You’re not.

"I’m proud of what I can do in my field. And I’m proud of the field. I don’t need any false additions to that. If I could write like John Cheever, I’d write like Cheever. Unfortunately I can’t, so I write as well as I can and as fast as I can. And some of it is good."

Gault, who grew up in Milwaukee, is a blue-collar novelist, a Depression kid and war veteran, an intelligent, self-educated man. In high school, he said, he had a car, so instead of buying books he bought gas. He was never academically eligible for sports; instead he had a gang. It took him seven years to graduate. He wrote poetry but would sign a girl’s name so his friends wouldn’t find out it was him.

Gault made his first magazine sales in 1936, to pulp magazines like Paris Nights and Scarlet Adventures, writing during the day, working in a shoe factory at night. He began full-time writing in 1939. He became a mainstay of the pulps, his byline appearing in more than 300 stories in Black Mask, Dime Mystery, Argosy and Street and Smith’s Detective Story magazine.

"It was a great time," Gault says. "We had a chance to learn our trade. The early pulp writers preempted Hemingway. The unfortunate thing was that Hemingway could write and they couldn’t. They got away from that florid prose of the Victorians to straight, almost journalistic writing. That’s why they don’t have to give you a Dickens description. They say three things and you know the character."

In 1949, Gault moved to Pacific Palisades. In California he joined the Fictioneers, a fraternal group to pulp writers that had been formed in the ‘30s and included W. T. Ballard, Henry Kutner, Day Keene, Bill Cox and Ray Bradbury. Gault’s closest friend was Fredric Brown, a frail intellectual who had also started out in Milwaukee. "Fred was the great, innovative one," Gault said. "He had a mind like Einstein and he peddled it for two cents a word."

Their pulp work was quick and playful. Brown wrote a story called "Whistler’s Murder" and Gault wrote one about a racehorse called "Whistler’s Mudder". On another occasion, they each wrote a story with the same last scene: five footsteps in the snow.

"Maybe the pulps will come back someday, but I don’t think so," Gault said. "They’re better than TV but they’re not enough better. No one’s going to turn off their tube for a chance to read."

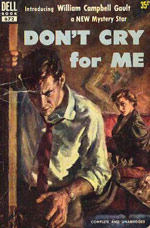

The pulps dying, Gault began working for the Post Office and worked on a novel at night. Fredric Brown, already an author with Dutton, sat in the firm’s office until editors read and agreed to publish Gault’s first book. "Don’t Cry For Me, written in 28 days, won an Edgar Award from the Mystery Writers of America. Then came Brock Callahan, a private investigator who would appear in 10 of Gault’s 25 mysteries. Callahan was one of the shrewdest and sexiest of the breed. Gault calls him "a self-appointed knight in tarnished armor."

The pulps dying, Gault began working for the Post Office and worked on a novel at night. Fredric Brown, already an author with Dutton, sat in the firm’s office until editors read and agreed to publish Gault’s first book. "Don’t Cry For Me, written in 28 days, won an Edgar Award from the Mystery Writers of America. Then came Brock Callahan, a private investigator who would appear in 10 of Gault’s 25 mysteries. Callahan was one of the shrewdest and sexiest of the breed. Gault calls him "a self-appointed knight in tarnished armor."

Coming up with a private eye series was usually a business decision suggested by agents and editors. The private investigators were the original fall guys, braving bullets, brass knuckles and fast women with nothing more than a wisecrack or two for protection. It was a tough business. They were beaten up and lied to. If they had any easy cases nobody wrote about them.

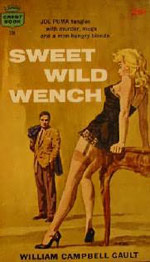

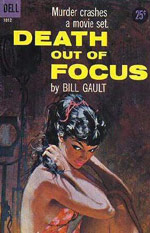

If things were muddled or confused the private eyes would sort things out, making them explicit and ordered. In their heyday, during a more simple time, they were the most efficient of social arbiters, judges, juries, all in one. Gault created two of them, Callahan and Joe Puma, introduced in 1958. "It’s the individual man," he said. "It’s a revolt against the conglomerate man, just one dirty guy doing a seedy job in a miserable world."

But in 1962 the mysteries stopped. Gault was tired of the Callahan series, bored with mysteries. "You can’t write 25 or 50 classic mysteries," he said. "It’s not possible." He was making three times the money on his 34 juvenile novels, which would stay in print. There was also a series novel, still unpublished, the story of a pulp writer who comes to California and breaks up with his wife, a plot that is not autobiographical in those details.

While pulp writers like Frank Gruber and Steve Fisher were going into the motion picture industry and moving to estates in Bel Air, Gault kept Hollywood and its riches at arm’s length. "I didn’t feel at home," he said. "You go to lunch and this guy’s talking 15 million, this guy’s talking 12 million, this guy’s talking 7 million and you’re sitting there with $12 in your pocket. Then the bill comes and you’re the only guy with 12 bucks. I don’t like it. I like to sit in a room and write. I’m never going to be rich."

While pulp writers like Frank Gruber and Steve Fisher were going into the motion picture industry and moving to estates in Bel Air, Gault kept Hollywood and its riches at arm’s length. "I didn’t feel at home," he said. "You go to lunch and this guy’s talking 15 million, this guy’s talking 12 million, this guy’s talking 7 million and you’re sitting there with $12 in your pocket. Then the bill comes and you’re the only guy with 12 bucks. I don’t like it. I like to sit in a room and write. I’m never going to be rich."

Gault lives simply with his wife of 42 years, Virginia, in a one-story stucco in a suburb of Santa Barbara, a city with more than its fair share of mystery writers. His office is an add-on in the garage with a desk and typewriter in one corner. For inspiration, he has a George Bellows boxing print and a book of Edward Hopper reproductions.

It was when the juvenile books stopped selling, that Gault went back to the mysteries. A fourth new Callahan mystery will be out next spring and a fifth is in Gault’s typewriter. In 1955 Callahan was in his early 30s. Today that would make him ... "around 40," Gault says. "It gets me. A guy says, "Well, how old is he now?’ But how old is Little Orphan Annie? She’s 112, isn’t she? How old is Ellery Queen? Callahan is an able-bodied man. I don’t want him to be 60. He’s still looking at the girls in their summer dresses but he’s not making a move, see?"

Today the fictional Callahan is wealthy and semi-retired, married to Jan Bonnet, a successful interior designer who cons Brock into ferrying her fabric samples around during his cases. He has ulcers.

Gault and Callahan share a satirical political point of view and the same enthusiasms: Dick Cavett, golf, "The Great Gatsby" and automobiles. Both have trouble reading Faulkner and Bartoleme. Both hate pretension, smog and opportunists.

On Tuesdays, Gault plays golf, a long-standing passion. On Thursdays, he goes shopping with Virginia. He teases her, accuses her of being a taskmaster along the lines of Perry White, Clark Kent’s demanding editor in the Superman series. Every other Wednesday he spends his lunch hour with a group of writers at a nearby restaurant. He has no schedule for his work. He just sits down and begins writing. If he’s hot, he writes all day. Usually he writes a book in three or four months. He aims for three or four pages a day.

"I think the ultimate mistake is in assuming that you can be a great writer if you are an intellectual and that you are an intellectual if you are a writer," he says. "There are some very great writers who are intellectually -- I’m sure -- dumb. And there are some great intellectuals who can’t write home for money. I think Shakespeare wrote real well and I’m sure that he didn’t just sit around at the academy and talk to scholars. He was in the bar, drinking and wenching. It wasn’t hard to write like Shakespeare. It was easy or it was impossible. It couldn’t have been hard. He just happened to have talent."

###

Copyright © David Laurence Wilson 1984

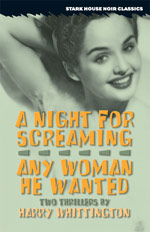

DAVID LAURENCE WILSON, who lives in the Tahoe National Forest, is a nonfiction writer who has written hundreds of articles for newspapers and magazines. He was a frequent contributor to the West Coast Review of Books and Book Editor of the Los Angeles Free Press. He was also an editor and contributor to the Close-Up on Film series (Scarecrow Press) and the McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of Western and Frontier Fiction. He wrote the introduction to the new Stark House Press edition of Harry Whittington's Night For Screaming/Any Woman He Wanted and the forthcoming Gil Brewer double The Three-Way Split/A Devil For O'Shaughnessy (the latter being previously unpublished), and is working on additional volumes of Whittington, W.R. Burnett and Wade Miller. He is also completing a collection of interviews with twenty-five classic U.S. crime writers, a thirty-year effort including interviews with Gault, W. R. Burnett, Richard Sale, Jonathan Latimer and Dorothy Hughes.

Contact David