- Welcome

- Noir Zine

- Allan Guthrie

- Books

"...those who enjoy the darker side of the genre are in for some serious thrills with this..."

Laura Wilson, The Guardian

Published in the UK by Polygon (March 19th, '09) and in the US by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (Nov '09).

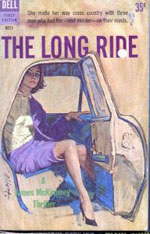

THE LONG RIDE

by James McKimmey

chapter eight

His single suitcase was resting on the rack at the foot of the bed. He opened it and looked at it carefully. Socks had been rolled into pairs, the top of one fitted around the whole to make a neat bundle. The bundles were carefully lined in a tight row. White shorts and T-shirts had been similarly rolled and fitted in absolute rows. Everything in that bag was precisely placed, including his gun, and Harry Wells was ready for a complete showdown inspection any second. The iron, the item that severely weighted the bag, was at the back end of the bag. He removed it and placed it on the top of a bureau. Then he took out a thick, browned length of heavy cloth that he used to place over whatever surface he used for his pressing.

His single suitcase was resting on the rack at the foot of the bed. He opened it and looked at it carefully. Socks had been rolled into pairs, the top of one fitted around the whole to make a neat bundle. The bundles were carefully lined in a tight row. White shorts and T-shirts had been similarly rolled and fitted in absolute rows. Everything in that bag was precisely placed, including his gun, and Harry Wells was ready for a complete showdown inspection any second. The iron, the item that severely weighted the bag, was at the back end of the bag. He removed it and placed it on the top of a bureau. Then he took out a thick, browned length of heavy cloth that he used to place over whatever surface he used for his pressing.

He removed his billfold, Zippo lighter, keys and change from his pockets, then took off his suit and shirt and underwear, standing in lean, bare hardness. He hung the suit in the closet. He wouldn’t, he thought, do any pressing until tomorrow, so he would be leaving here with everything in its best shape.

He carried his shirt and underwear into the bath and filled the washbasin with lukewarm water, to let the clothing soak. Then he returned to his suitcase and removed a large bar of Ivory soap; you couldn’t beat Ivory, he’d decided a long time ago, for the suds. Finally he took out a clean T-shirt and a pair of shorts and placed them carefully on the bag. Before he snapped the bag shut, he looked at the gold-framed picture he’d placed on the bottom of the bag. He took it out, careful to rearrange the socks he’d disturbed.

It was a picture of himself in khakis faded almost to white from the sun and constant washing; there was a short strip of neatly laced leggings beneath the bloused trousers, and his hair was clipped neatly at the temples. He’d looked very lanky, brown and bone-young. He’d been a staff sergeant then, and you could see the stripes on the sleeve the girl was holding with one possessive hand. The girl was small, dark, with high cheekbones and large, animal-bright eyes; she had long black hair and wore a thin dress that showed the good lift of her breasts, the thick, ripe set of her hips. The picture had been taken in Panama in 1943.

He placed the picture on the bureau and returned to the bath, to hand-scrub the clothing in the sink. A long time ago, Panama and Pooli. Pooli – what a name. But she’d been fine. Part French, part Chinese, part Spanish, part Indian – the best of all of those bloods. Panama had been no good otherwise. Stinking hot, and he’d been nervous down there in an RA garrison, drinking PX beer and local rum, while the war got into a full-scale operation.

But there’d been Pooli, eager, soft, lazy, spitting, seductive, abandoned, loving, all wrapped up into one little French-Chinese-Spanish-Indian girl.

How long had it been? Too long. She’d written him some pathetic letters in horrible grammar that had made even him wince. He’d never answered them. All he had to do was think of that stinking heat down there, and he didn’t even want to write to her. But she’d been the best woman he’d ever had, worth that fight he’d had in the beginning to get her.

He paused, soapy white shirt in hand, and remembered that Panamanian bar, dancing with Pooli, and that sergeant from another battalion who’d come up and announced Pooli was his and had been for six months. His eyes narrowed a little, as he remembered how they’d gone at it, all over that bar. How the sergeant, a tall, blond, blue-eyed, mean son of a bitch from New Jersey, had finally pulled a knife.

He’d really had to go for him then, smashing the bastard’s head with a bottle, finally slamming him against the railing of the bar. They carried him out of there. Dead. And he’d been ultimately glad for the knife, because the knife made it self-defense on his part. The Army hadn’t wanted trouble down there, and the bastard from New Jersey had a reputation for trouble. They hadn’t even put it on his record, let alone shaved his stripes.

He shrugged, dipping his shirt. Long time ago. But when he got this done, got the money form Garwith, he might go down and see how fat Pooli had gotten, how many illegitimate kids she had running around after her.

But, he thought, probably not. Too hot down there, even for a short visit. No, he was going where it was cool, where you could put on clean clothes and have them stay neat and fresh and well-pressed for hours. Alaska maybe. That sounded all right. Iceland, Norway, Sweden. Anywhere where you didn’t sweat all the time.

When he’d washed his clothes, he showered for twenty minutes, scrubbing and rinsing himself steadily. He stretched a cord from his bag between two chairs near a window and hung the clothes to dry. They would be just right for pressing in the morning, he thought.

Then he sat down on the bed in fresh shorts and T-shirt and put a cigarette between his lips, looking disdainfully at the basket containing the sandwiches. He snapped the Zippo lighter. It failed to light. He looked at it carefully.

He tried again, frowning. It failed again. Slowly he took it apart. The flint was all right. But he could see that the fluid was running out. He got the fluid can from his bag and soaked the cotton. He could see, because the fluid had run low, that the wick had burned down. But he didn’t have another wick.

He reassembled the lighter, attempting to lift the wick slightly, and tried once again. It sparked, but it wouldn’t light. He tried it over and over, a look of stubborn concentration in his eyes, a faint ache starting at the back of his head once more.

He took the lighter apart again, absently taking a sandwich from the basket beside him. He ate the sandwich. Then assembled the lighter and tried again. It wouldn’t work. He took it apart again, oblivious of the time. He worked for forty minutes, consuming the sandwiches, all of them, without realizing he had. Still the lighter wouldn’t work.

That impassive look of stubborn concentration never left his eyes. He assembled and reassembled the lighter, never working faster or slower than he had the first time. Finally he realized an hour had gone by. He placed the lighter on the night stand and turned out the lights and lay back in bed. He would have to get a wick somewhere tomorrow.

He closed his eyes; then, after a few minutes, he sat up and switched on the lights again. He picked up the lighter and took it apart again.

He looked very much as he had when he’d been sitting on his bunk one summer evening at Ford Dix in 1944, just before his division shipped overseas into combat. Then he’d been perplexed with a faulty ejector spring on his carbine. The rifle needed a new spring. He could have walked over to the supply room and gotten a new one. But instead he attempted to make the old one work. He’d repeatedly taken apart and reassembled the rifle’s mechanism, the same look in his eyes as he had now.

A twenty-year-old PFC named Brown, whose mother was dying in Biloxi, had sat and watched him. He watched him take apart and put together that mechanism fifty times. Brown, who had been refused an emergency furlough to watch his mother die because he’d already had one a month before when they thought she was going to die and hadn’t, kept opening and closing his hands as though wanting to help. He counted the process up to sixty, then got up and tore the rifle out of Wells’s hands and threw it against the barracks wall, screaming. They discharged the boy on a Section 8 that week, but his mother had died by the time he got back to Biloxi.

At eleven-thirty, Harry Wells studied his lighter once again, then tried it again. He watched the spark fail to catch in the too-short wick. Carefully he took the lighter apart again.

Copyright© 1961 James McKimmey

***