- Welcome

- Noir Zine

- Allan Guthrie

- Books

"...those who enjoy the darker side of the genre are in for some serious thrills with this..."

Laura Wilson, The Guardian

Published in the UK by Polygon (March 19th, '09) and in the US by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (Nov '09).

Femme Fatale: Women, Sex And Guilt In Noir Fiction

by Damien Seaman

Pity the poor femme fatale. I mean, would you want to be her? There you are, all set to get away with it, when the sap you’ve been conning successfully for the last two hundred pages suddenly rolls over and works out it was you. And you know that’s not good. If he doesn’t shoot you for killing his buddy [1] or hook you on smack [2] he’ll hand you over to the cops [3]. And for what? A measly few thousand dollars? The chance to get away from the brute who was sexually abusing you, or from the memory of the father who sexually abused you?

No, I wouldn’t want to be that woman.

Maleness, the idea of it and the reality of it, dominates noir fiction more than any other genre I can think of. Because of this, the treatment of women in noir can be unsettling. At best it betrays a range of psycho-sexual obsessions, at worst unthinking misogyny. Far from being a stereotype, the femme fatale is the key to understanding a woman’s place in the noir world. If she’s not the instigator of the crime, the spider in her web, then she’s a victim of male brutality or abuse.

So what’s it all about? Early noir establishes the parameters. Whether the woman is consciously innocent or guilty, she represents sexual temptation, playing the Eve to the protagonist’s Adam. Nowhere is this more evident than in Chandler’s Farewell, my Lovely, when Marlowe describes Helen Grayle as ‘A blonde to make a bishop kick a hole in a stained-glass window.’[4] In The Postman Always Rings Twice, James M Cain’s protagonist Frank Chambers fixates on Clara’s mouth: ‘Her lips stuck out in a way that made me want to mash them in for her’.[5] Later, he describes her as looking ‘like the great grandmother of every whore in the world’.[6]

So what’s it all about? Early noir establishes the parameters. Whether the woman is consciously innocent or guilty, she represents sexual temptation, playing the Eve to the protagonist’s Adam. Nowhere is this more evident than in Chandler’s Farewell, my Lovely, when Marlowe describes Helen Grayle as ‘A blonde to make a bishop kick a hole in a stained-glass window.’[4] In The Postman Always Rings Twice, James M Cain’s protagonist Frank Chambers fixates on Clara’s mouth: ‘Her lips stuck out in a way that made me want to mash them in for her’.[5] Later, he describes her as looking ‘like the great grandmother of every whore in the world’.[6]

Behind the sexy femme fatale image lies the male’s cry that woman is the cause of all his grief. Postman’s Frank says to Clara, ‘"You must be a hellcat, though. You couldn’t make me feel like this if you weren’t."’[7] When Joe Marlin in Lawrence Block’s Grifter’s Game realises he’s been had, he confronts the woman he killed for: ‘"You acted so perfectly I fell on my face."’[8] In Jason Starr’s Hard Feelings, Richard Segal accuses his wife: ‘"You’re always lying to me!...Even when you say you’re on my side, you’re still lying!"’[9] In Bust, the book Starr co-wrote with Ken Bruen, Max Fisher has his wife killed so he can marry his secretary Angela. Yet by the end of the book Angela has been hospitalised and Fisher is thinking, ‘Why wouldn’t the bitch do the decent thing and fuckin’ die?’[10]

In opposition to these harlots is the code of honour which binds men together in spite of their differences. Take the best example of this, The Maltese Falcon, when Sam Spade hands Brigid O’Shaughnessy to the police for killing his partner, Miles Archer. Spade doesn’t even like Archer, describing him as ‘"a son of a bitch"’. But ‘"when a man’s partner is killed he’s supposed to do something about it. It doesn’t matter what you thought of him."’[11] It’s the same in Ted Lewis’ Get Carter. Jack Carter returns to south Yorkshire to avenge the death of his brother despite the antipathy between them. Just because ‘"He was my brother."’ [12] Ken Bruen explores similar territory in The Guards. Jack Taylor’s friendship with Sean the pub owner is close and mysterious to outsiders, his sexual relationship with Ann Henderson fraught with misunderstanding and the certain knowledge that each will disappoint the other. Is it any wonder Spade tells Brigid, ‘"You’ll never understand me’"? [13] Or that the femme fatale would rather take the money and run?

If there is a hard and fast philosophy underpinning all these betrayals and quarrels then the lack of understanding must be it. And what is the root of this inability to see eye to eye? Sex, of course. Wherever the femme fatale exists in noir, sex and sexual obsession are sure to follow. Don’t believe me? Just think of how often sexual themes keep cropping up. Prostitution features in the work of Jason Starr (Cold Caller), Ted Lewis (Get Carter), Allan Guthrie (Kiss Her Goodbye) and James Ellroy (the LA Quartet). [14] Ellroy and Lewis’ books also feature pornography, as does Chandler’s The Big Sleep. [15] Incest and other forms of sexual or psycho-sexual abuse can be found in the work of Jim Thompson (The Grifters, A Swell-Looking Babe) and Lawrence Block (Grifter’s Game), as well as in Ellroy and Guthrie again, [16] while straight ahead sexual obsession is there in James M Cain (The Postman Always Rings Twice, Double Indemnity) and Patricia Highsmith (This Sweet Sickness, The Cry of the Owl). Oh, and Ellroy again. [17]

If there is a hard and fast philosophy underpinning all these betrayals and quarrels then the lack of understanding must be it. And what is the root of this inability to see eye to eye? Sex, of course. Wherever the femme fatale exists in noir, sex and sexual obsession are sure to follow. Don’t believe me? Just think of how often sexual themes keep cropping up. Prostitution features in the work of Jason Starr (Cold Caller), Ted Lewis (Get Carter), Allan Guthrie (Kiss Her Goodbye) and James Ellroy (the LA Quartet). [14] Ellroy and Lewis’ books also feature pornography, as does Chandler’s The Big Sleep. [15] Incest and other forms of sexual or psycho-sexual abuse can be found in the work of Jim Thompson (The Grifters, A Swell-Looking Babe) and Lawrence Block (Grifter’s Game), as well as in Ellroy and Guthrie again, [16] while straight ahead sexual obsession is there in James M Cain (The Postman Always Rings Twice, Double Indemnity) and Patricia Highsmith (This Sweet Sickness, The Cry of the Owl). Oh, and Ellroy again. [17]

Indeed, at times Ellroy’s work reads like a multi-volume encyclopaedia of every form of obsession the male can have with the female. At the heart of this lies Ellroy’s belief that sexual psychoses are inevitable in a paternalistic society; and that although these might wound men and women alike, women naturally come off worse. Time and again in the LA Quartet he embodies this theme in the form of the corrupt, ambitious father figure. Perhaps Ellroy’s psychological insight stems from his self-documented fascination with the death of his mother. [18] It certainly makes for compelling reading.

The Black Dahlia contains perhaps the most notorious example of Ellroy’s worldview. In this book, violent sexual obsession leads to the death and mutilation of budding actress Elizabeth Short. But the murderer turns out to be a victim too, at least in the psychological sense. [19] And then there’s the case of Officer Bud White from LA Confidential. As the novel opens he is a man on a mission to rescue battered wives. He also takes on a private case to apprehend a serial killer who is targeting prostitutes. But in spite of his obsession with saving vulnerable women, he cannot escape the violent tendencies brought out under the tutelage of surrogate father figure Dudley Smith. In particular, he cannot stop himself from beating up his prostitute girlfriend Lynn when he discovers she has slept with his arch-rival Ed Exley. [20]

The Black Dahlia contains perhaps the most notorious example of Ellroy’s worldview. In this book, violent sexual obsession leads to the death and mutilation of budding actress Elizabeth Short. But the murderer turns out to be a victim too, at least in the psychological sense. [19] And then there’s the case of Officer Bud White from LA Confidential. As the novel opens he is a man on a mission to rescue battered wives. He also takes on a private case to apprehend a serial killer who is targeting prostitutes. But in spite of his obsession with saving vulnerable women, he cannot escape the violent tendencies brought out under the tutelage of surrogate father figure Dudley Smith. In particular, he cannot stop himself from beating up his prostitute girlfriend Lynn when he discovers she has slept with his arch-rival Ed Exley. [20]

As these examples from Ellroy show, if sex itself underpins the battle of the sexes, we should expect noir authors to tackle the subject the way they tackle everything else: with an unflinching eye. For noir stands or falls on its ability to ask uncomfortable questions of society. If society – particularly criminal society – is sex-obsessed or misogynistic then this is likely to come out in noir fiction. And since humanity cannot seemingly escape its own dark nature, in noir fiction the darker side of desire is played out. Thus we not only read of sexual attraction, but also obsession; not just unrequited love, but also rape; the sexual abuse of children. The list goes on. Sometimes the author will do this unconsciously, more often deliberately. Get Carter, for instance, is particularly dogged in its attitude towards women. All the women in this book come across as ‘slags’ of one sort or another, well-versed in the rules of the sexual game. [21] But is Lewis making a point about women, about the views of self-made hard men like Jack Carter, or about British society?

It is easy to lay the charge at the door of male-dominated noir that these themes are male themes; that sexual obsession and the exploitation of women are a result of authors giving in to their own dark natures, and that noir novels about women and sex expose the subconscious desires and guilt of the authors. But this is an over-simplified view. Men should not be disqualified from writing about sex or about women because they are men. And fiction is not autobiography. Just because a male author writes about rape or wife beating does not mean he has a latent desire to commit them. And yet these crimes do take place, and isn’t it the role of great fiction to seek out the truth, however subjective, and to ask why these crimes persist?

Hand in hand with authors asking questions of modern society go characters who question their own motivations. Some do this more reluctantly than others, but they still do it. So while male protagonists can and do blame their women for their troubles, in the end most of them also acknowledge their own complicity, even if only subconsciously. If, in Postman, Cora incites Frank to murder for her on page 16, Frank admits to planning the murder and to getting the idea ‘from a piece in the paper…’ [22] And Frank also realises the role of the subconscious in his actions: ‘Did I really do it, and not know it? God Almighty I can’t believe that!’ [23] The same is true of Walter Neff in Cain’s Double Indemnity. Like Frank, Walter knows what he’s getting into even as he falls into the trap. [24] Ultimately, Cain sets up these men as flawed, even pathetic, examples of masculinity. They murder because they are in thrall to their sexual desires. Deep down Frank and Walter know what kind of men they are, and they blame their women as a way of coming to terms with this.

By contrast, Hammett’s Spade knows he is responsible for his actions. As The Maltese Falcon ends we see his secretary Effie, a character we have been led to admire, turn against him for handing Brigid to the police. When Effie asks Spade not to touch her, Spade accepts her judgement and his face goes pale. Then he shivers when he realises he must still deal with the consequences of his longstanding affair with Archer’s wife, Iva. She turns up at several points throughout the novel as a reminder of Spade’s corrupt nature. [25] When she returns at the end of the book the reader is taken full circle to her first appearance – to the notion of Spade as Hammett’s ‘blond satan’. [26] Hammett’s two-fold message seems clear: O’Shaughnessy uses her wits and her feminine charms to get through life because they are all she has. Spade recognises her for who she is because he and she are the same: cynical and corruptible, with a hard shell to protect the lost, lonely individual within.

By contrast, Hammett’s Spade knows he is responsible for his actions. As The Maltese Falcon ends we see his secretary Effie, a character we have been led to admire, turn against him for handing Brigid to the police. When Effie asks Spade not to touch her, Spade accepts her judgement and his face goes pale. Then he shivers when he realises he must still deal with the consequences of his longstanding affair with Archer’s wife, Iva. She turns up at several points throughout the novel as a reminder of Spade’s corrupt nature. [25] When she returns at the end of the book the reader is taken full circle to her first appearance – to the notion of Spade as Hammett’s ‘blond satan’. [26] Hammett’s two-fold message seems clear: O’Shaughnessy uses her wits and her feminine charms to get through life because they are all she has. Spade recognises her for who she is because he and she are the same: cynical and corruptible, with a hard shell to protect the lost, lonely individual within.

Again, if the early noir masters established the notion of the male’s complicity in his own downfall, the writers who followed repeated the pattern. Block’s Joe Marlin, Starr’s Richard Segal and Bruen’s Jack Taylor are all more than aware of their own failings. Each of these protagonists is a variation on the theme of male weakness. [27]

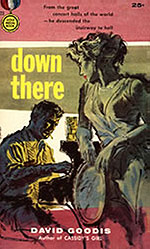

According to this theory then, we can see the femme fatale as a device designed to expose and even exploit this weakness. Of course, this could still constitute a misogynistic worldview: for some noir authors the lesson remains ‘beware the female of the species!’ But many femmes fatales are also admirable characters. Block’s Evelyn Stone in The Girl with the Long Green Heart gets away with beating two experienced male con artists at their own game. [28] Other feisty female characters taking on the femme fatale mantle can influence events through sheer force of will. David Goodis’ waitress Lena in Shoot the Piano Player is a good example of this. So is Allan Guthrie’s prostitute Tina/Ruth in Kiss Her Goodbye. In both of these books the gutsy women end up influencing the male protagonists’ actions for the better. [29]

According to this theory then, we can see the femme fatale as a device designed to expose and even exploit this weakness. Of course, this could still constitute a misogynistic worldview: for some noir authors the lesson remains ‘beware the female of the species!’ But many femmes fatales are also admirable characters. Block’s Evelyn Stone in The Girl with the Long Green Heart gets away with beating two experienced male con artists at their own game. [28] Other feisty female characters taking on the femme fatale mantle can influence events through sheer force of will. David Goodis’ waitress Lena in Shoot the Piano Player is a good example of this. So is Allan Guthrie’s prostitute Tina/Ruth in Kiss Her Goodbye. In both of these books the gutsy women end up influencing the male protagonists’ actions for the better. [29]

A re-reading of the male code of honour throws up similar subtleties. Jason Starr’s protagonists are as suspicious of other men as of women. In an interesting twist, the motive for murder in Hard Feelings is Segal’s half-remembered childhood experience of sexual abuse at the hands of another man. [30] But is this a subversion of the traditional male bond, or its logical conclusion? Patricia Highsmith takes this idea further in Strangers on a Train, where Bruno’s attachment to Guy soon takes on obsessive homosexual undertones. [31] Guthrie also turns the male bond on its head in Kiss Her Goodbye, when Joe Hope’s faith in his friend Cooper turns out to be the cause of all his troubles. [32] David Goodis makes clear in Shoot the Piano Player that Eddie Lynn’s bond with his wayward brothers is the cause of his lifelong bad luck. For Eddie the male code spells nothing but trouble. [33]

So on the one hand our femme fatale is the male nemesis, there to exploit his failings. But on the other she is someone he can turn to in difficult times. In the cases of Lynn Bracken in Ellroy’s LA Confidential, Lena in Goodis’ Shoot the Piano Player, or Carol McCoy in Jim Thompson’s The Getaway, these turn out to be good choices for the protagonist, regardless of how events pan out. In all of these examples the so-called femme fatale becomes a trusted companion, a loyal lover, even – whisper it – an equal. Doesn’t Doc’s wife come up with the plan to spring him from jail in The Getaway? [34] Doesn’t Lena clear Eddie’s name in Shoot the Piano Player? [35] And doesn’t Lynn give Bud White the faith to keep from imploding in LA Confidential? [36]

So on the one hand our femme fatale is the male nemesis, there to exploit his failings. But on the other she is someone he can turn to in difficult times. In the cases of Lynn Bracken in Ellroy’s LA Confidential, Lena in Goodis’ Shoot the Piano Player, or Carol McCoy in Jim Thompson’s The Getaway, these turn out to be good choices for the protagonist, regardless of how events pan out. In all of these examples the so-called femme fatale becomes a trusted companion, a loyal lover, even – whisper it – an equal. Doesn’t Doc’s wife come up with the plan to spring him from jail in The Getaway? [34] Doesn’t Lena clear Eddie’s name in Shoot the Piano Player? [35] And doesn’t Lynn give Bud White the faith to keep from imploding in LA Confidential? [36]

The femme fatale is a male image of the female, particularly the sexually-attractive female. But, as we have seen, she is not always the scheming secretary, or the mystery woman with a shady past. She can be any kind of woman, and any kind of woman can take on the mantle of femme fatale, because however real and well-drawn as a character, she is also a symbol of womanhood and of the battle of the sexes. Whether this symbolism bothers you probably depends on how you see noir fiction in the first place. If you see noir as crude and limited, then you will see the femme fatale as a crude and limited stereotype. If, on the other hand, you can see noir for what it is – a legitimate art form which can be brash and shocking or subtle and melancholy and everything in between – then you will also see the femme fatale for who she is. An empowered woman using her charms and intelligence to get what she wants. The equal of her male protagonist, and someone to be very wary of. After all, she doesn’t always get caught.

###

Copyright © Damien Seaman 2007

Click here to read an extract from Damien Seaman's novel, 5 From 7

NOTES:

1) See Mikey Spillane, I, the Jury (Signet, 1947)

2) Lawrence Block, Grifter’s Game (Hard Case Crime, 2004; originally published as Mona, 1961)

3) Dashiell Hammett, The Maltese Falcon (Knopf, 1930)

4) Raymond Chandler, Farewell, My Lovely (in Chandler: Stories and Early Novels, Library of America, 1995; Farewell, My Lovely originally published by Knopf, 1940) p. 834

5) James M Cain, The Postman Always Rings Twice (Vintage Crime/Black Lizard edition, 1992; originally published by Knopf, 1934) p. 4

6) ibid., p. 87

7) ibid., p. 17

8) Lawrence Block, Grifter’s Game (Hard Case Crime, 2004) p. 192

9) Jason Starr, Hard Feelings (No Exit Press, 2003) p. 189. The New York Times Book Review has described Starr’s characters as ‘brittle’ and ‘selfish’, and I have yet to find a better description. Starr could be the most convincing purveyor of white collar desperation writing today. Check him out if you haven’t already – anyone who’s ever worked in an office will cringe with recognition.

10) Ken Bruen and Jason Starr, Bust (Hard Case Crime, 2006) p. 234

11) Dashiell Hammett, The Maltese Falcon (in Hammett: Complete Novels, Library of America, 1999; The Maltese Falcon originally published by Knopf, 1930) p. 581

12) Ted Lewis, Get Carter (Allison & Busby, 1998; originally published as Jack’s Return Home by Michael Joseph Ltd, 1970) p. 124

13) Dashiell Hammett, The Maltese Falcon (Library of America, 1999) p. 581

14) Jason Starr, Cold Caller (No Exit Press, 1997) pp. 67-70; Ted Lewis, Get Carter (Allison & Busby, 1998) pp. 53, 83,140; Allan Guthrie, Kiss Her Goodbye (Polygon, 2006); James Ellroy, LA Confidential (Arrow, 1990): Lynn Bracken is part of Pierce Patchett’s high-class prostitution ring, while male prostitution is also referenced, for example p. 465.

15) James Ellroy, LA Confidential (Arrow, 1990) - since Jack Vincennes ends up working Ad Vice, the novel is full of references to ‘smut books’, which begin pp. 101-110; Ted Lewis, Get Carter (Allison & Busby, 1998) pp. 162-166; Raymond Chandler, The Big Sleep (in Chandler: Stories and Early Novels, Library of America, 1995; The Big Sleep originally published by Knopf, 1939). On pp. 613-615 and p. 619 Marlowe discovers Carmen Sternwood has been drugged and had pornographic pictures taken of her. Later, Marlowe shoos Carmen out of his bed after refusing to sleep with her. ‘The imprint of her head was still in the pillow, of her small corrupt body still on the sheets. I put my empty glass down and tore the bed to pieces savagely.’ Now that’s a strong reaction.

16) Jim Thompson, The Grifters (Vintage Crime/Black Lizard, 1990); Jim Thompson, A Swell-Looking Babe (Vintage Crime/Black Lizard, 1991); Lawrence Block, Grifter’s Game (Hard Case Crime, 2004), during the book’s dynamite denouement; James Ellroy, White Jazz (Arrow, 1992) p. 29; Allan Guthrie, Kiss Her Goodbye (Polygon, 2006), see p. 35, or pp. 90-98.

17) James M Cain, The Postman Always Rings Twice (Vintage Crime/Black Lizard edition, 1992), see notes [5], [6] and [7] above; James M Cain, Double Indemnity (Knopf, 1935); Patricia Highsmith, The Cry of the Owl (1962); Patricia Highsmith, This Sweet Sickness (1960); see Ed Exley’s dalliance with Lynn Bracken in LA Confidential pp. 362-363 – the question is, is Exley after Lynn, or after Bud White through Lynn?

18) James Ellroy, My Dark Places (Arrow, 1996)

19) James Ellroy, The Black Dahlia (Arrow, 1987). The murder is discovered on p. 87 and the murderer on pp. 366-375. But Bucky can’t bring himself to charge her with the Dahlia murder, maybe because of how psychologically damaged she is. On p.378 court psychiatrists find the murderer to be ‘"a severely delusional violent schizophrenic"’: a classic example of Ellroy’s damaged goods.

20) James Ellroy, LA Confidential (Arrow, 1990). Bud White’s vendetta against abusive husbands becomes clear pp. 11-13, and he beats Lynn on p. 386.

21) Ted Lewis, Get Carter (Allison & Busby, 1998) p. 52. There are dozens of examples of this. Possibly the most notorious is Jack’s cool appraisal of the sexual charms of his own niece, a fifteen year old who, we later learn, might even be his daughter: ‘I could have fancied her myself…you could tell she knew what was what. In her eyes…’ p. 26. Or take p. 85, when a woman starts a fight with a stripper in a bar. The stripper’s crime? Flirting with the woman’s bloke by dangling her nipple in his pint. The two women end up wrestling on the floor. The bloke then pours beer on the women, as though to cool down a couple of bitches in heat. See also Jack’s constant references to women being the ‘right’ or the ‘wrong’ side of 40.

22) James M Cain, The Postman Always Rings Twice (Vintage Crime/Black Lizard edition, 1992). On p. 16, when Cora asks Frank if he’ll help her kill her husband, Frank replies, ‘"Did you say you weren’t really a hell cat?"’. Frank might tell us that Cora talked him into it, but he knew what he was getting into all right. See p. 19 where he boasts about his murder plan.

23) ibid., p. 116. The relevant passage is so good it’s worth quoting at length: ‘There’s a guy in no. 7 that murdered his brother, and says he didn’t really do it, his subconscious did it. I asked him what that meant, and he says you got two selves, one that you know about and the other that you don’t, because it’s subconscious. It shook me up. Did I really do it, and not know it? God Almighty, I can’t believe that!’ But his denial is all bluster: he does believe it.

24) James M Cain, Double Indemnity (Knopf, 1935)

25) Dashiell Hammett, The Maltese Falcon (Library of America, 1999) pp. 584-585. Effie’s disgust is the first time in the book anyone succeeds in breaking through Spade’s tough exterior, and it’s an unsettling moment for the reader. It’s the first time you wonder whether Spade is really as cool as you thought he was. When he shivers at the thought of seeing Iva again, resigned to the fact he must, it shows him up as a real man with real weaknesses, and a particular weakness for the opinion of the women in his life. In this, Spade is a reflection of Hammett himself, who loved the company of women.

26) ibid., p. 391. In fact, Hammett tells us, he looked ‘rather pleasantly like a blond satan’ [my italics], which should tell us all we need to know about the author’s intentions with this character – this is a man who is going to challenge our preconceptions and probably get away with it. Archer’s wife puts in her first appearance on p. 409.

27) Lawrence Block, Grifter’s Game (Hard Case Crime, 2004); Jason Starr, Hard Feelings (No Exit Press, 2003); Ken Bruen, The Guards (St. Martin’s Press, 2001). There’s a particularly good paragraph on p. 226 of The Guards which captures this mixture of self-deception and self-knowledge: ‘I rang Ann, felt if I could just see her, we might have a shot. As soon as she heard my voice, she hung up. My beard was full arrived, complete with grey flashes. Told myself it spoke of character, even maturity. Odd times I caught my reflection, I saw the face of desperation.’

28) Lawrence Block, The Girl with the Long Green Heart (Hard Case Crime, 2005; originally published by Fawcett Publications, 1965). There’s more than a hint of admiration in protagonist Johnny Hayden’s reflections on p. 228: ‘I thought about that warm woman and how well I’d been had. I had never felt so much like a mooch.’

29) Shoot the Piano Player depicts the femme fatale’s conversion from inconvenience to saviour in the space of a few pages. On p. 120 Eddie thinks of Lena as ‘This complication…She comes along with her face and her body and before you know it you’re hooked.’ But by p. 124 he’s changed his tune: ‘She’d stick with you right through to the windup. She’s made of that kind of material. Maybe once in a lifetime you find one like this.’ In a similar vein, Kiss Her Goodbye portrays Tina’s shift from hard-nosed whore to fully-fledged ally. Page 69 sees Tina considering blackmailing Joe when she learns his real name. By p. 176 she is placing her hand on Joe’s shoulder to offer moral support as he passes by. And by the end of the book she helps stop Joe from killing himself or Cooper.

30) Jason Starr, Hard Feelings (No Exit Press, 2003)

31) Patricia Highsmith, Strangers on a Train (Penguin, 1972; originally published by Harper & Brothers, 1950). See pp. 174-182. Even as the novel opens, Bruno’s proposition comes across as a kind of crude seduction, pp. 7-32. This, Highsmith’s first novel, is just the first of her variations on the theme of unhealthy sexual obsession. See also The Cry of the Owl (1962), This Sweet Sickness (1960) or The Talented Mr Ripley (1955).

32) And how! Cooper sexually abuses Joe’s daughter, causing her to commit suicide. Then he frames Joe for the murder of Joe’s wife. It then turns out Cooper and she had been ‘"fucking each other’s brains out since university"’ (p. 230). Allan Guthrie, Kiss Her Goodbye (Polygon, 2006). With friends like these…

33) David Goodis, Shoot the Piano Player (Vintage Crime/Black Lizard, 1990; originally published by Fawcett Publications, 1956). See p. 146 when Eddie’s brother Clifton tells him, ‘"You hadda come back. You’re one of the same Eddie. The same as me and Turley. It’s in the blood."’ Or p. 150, when Eddie tells Lena he can’t leave his brothers to go back to Philly with her without telling them. It is this action which brings about the final set piece of the book in all its brute irony. Thurley’s abrupt entrance at the beginning of the novel knocks Eddie’s life out of kilter, while Eddie’s contact with Clifton at the end of the novel helps reinforce his isolation.

34) Jim Thompson, The Getaway (Vintage Crime/Black Lizard 1994; originally published by Signet, 1959) p. 46. It’s tempting to see Carol as a bungling amateur, which of course she is. But then so is Doc himself when he fails to kill Rudy, not to mention in bringing Carol in on a bank job she’s not ready for. This isn’t a book about the femme fatale bringing down her man, but about two people in love struggling against the vagaries of fate. From the time Doc makes it out of jail, he and Carol are doomed.

35) David Goodis, Shoot the Piano Player (Vintage Crime/Black Lizard, 1990) p. 148

36) James Ellroy, LA Confidential (Arrow, 1994). Lynn sums up her choice of partner at the end of the novel on p. 479 by comparing Ed Exley to Bud White: ‘"I can’t believe it. I’m giving up a hotshot with seventeen million dollars for a cripple with a pension"’. Ellroy has probably done more than most to rehabilitate the general public’s perception of the femme fatale as a complex character. His sophisticated exploration of sexual relationships in the LA Quartet (The Black Dahlia, 1987; The Big Nowhere, 1988; LA Confidential, 1990; and White Jazz, 1992) is well worth checking out. Just make sure you read The Black Dahlia before seeing the film. Or, better, just skip the film altogether and watch something good instead, like Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity (1946).

Born in Mansfield, UK and baptised in Libya, DAMIEN SEAMAN has vomited orange juice on infamous English football coach Brian Clough and smuggled illegal bacon and booze into Kuwait, his most criminal act to date. He has worked in European politics, edited a newspaper and been a security guard, after which he worked in an egg factory, a pizza factory, a salad factory and a fruit factory, but not all at the same time. An unspectacular stint as a Tesco management trainee helped speed his current exile to Berlin, where his hobbies include learning German and going to work. More of his crime fiction is forthcoming at Pulp Pusher and Spinetingler Magazine.

Contact Damien