- Welcome

- Noir Zine

- Allan Guthrie

- Books

"...those who enjoy the darker side of the genre are in for some serious thrills with this..."

Laura Wilson, The Guardian

Published in the UK by Polygon (March 19th, '09) and in the US by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (Nov '09).

Classic Noir Fiction into Film: The celebration of rot

by Terry White

"[Noir is] the moral phenomenology of the depraved or ruined middle classes."

—Mike Davis, City of Quartz

Like many fans of noir fiction and film, I have always been curious about the reasons behind filmmakers’ choices when it come to which novels to adapt. On that basic level as filmgoer, which is where fans like me usually operate from, I respond to some filmed novels like the museum buffoon who doesn’t know what it is exactly but he sure knows what he likes. I often wonder why some films are not made from novels that strike me as having greatest potential. Chandler’s The Little Sister pops to mind as do those long-neglected novels of Ross Macdonald, one of the best of the modern noirists. Then, again, I wonder why some great novels are treated so shabbily in film. The biggest question of all is reserved for those films which should never have been made. What kind of group hysteria, for example, must have possessed a pod of humorless moguls, investment capitalists, and producers to bankroll an ugly travesty like The Soft Kill?

I’ve always thought Ross MacDonald’s Lew Archer deserved a better filmic fate than he has ever received, no apologies to Paul Newman’s pre-geriatric performance in 1975’s Harper and his later somnambulistic one in The Drowning Pool. Though Macdonald would die too soon of Alzheimer’s in 1983, he already had a respectable body of work with classics like The Chill (1964) and The Underground Man (1971). Yet no filmed version of any of his great novels strands alongside Double Indemnity or The Postman Always Rings Twice to keep his name alive to moviegoers despite his high value to noir literature. But, note well, the greats have suffered, too. Take, for instance, Raymond Chandler’s The High Window (retitled The Brasher Doubloon in America and previously filmed as Time to Kill), a low-budget, lackluster effort in 1936 that would reign as the poorest Chandler adaptation until 1973 when Elliott Gould appeared in a shambolic rendering of The Long Goodbye. By the way, Robert Altman’s shabby duplication of Chandler deserves its low esteem. Charles Champlin described Gould’s rendering of Marlowe as "an unshaven semi-literate dimwit slob who could not locate a missing skyscraper," a criticism still apt (qtd. in Halliwell’s 449). Shane Black, another veteran scriptwriter alongside Robert Towne (Chinatown) and William Goldman, paid a curious homage (besides the title) to this ugly film in The Long Kiss Goodbye with Gina Davis and Samuel L. Jackson. There’s a television set in their hotel room playing the grocery store scene from the Altman film.

I’ve always thought Ross MacDonald’s Lew Archer deserved a better filmic fate than he has ever received, no apologies to Paul Newman’s pre-geriatric performance in 1975’s Harper and his later somnambulistic one in The Drowning Pool. Though Macdonald would die too soon of Alzheimer’s in 1983, he already had a respectable body of work with classics like The Chill (1964) and The Underground Man (1971). Yet no filmed version of any of his great novels strands alongside Double Indemnity or The Postman Always Rings Twice to keep his name alive to moviegoers despite his high value to noir literature. But, note well, the greats have suffered, too. Take, for instance, Raymond Chandler’s The High Window (retitled The Brasher Doubloon in America and previously filmed as Time to Kill), a low-budget, lackluster effort in 1936 that would reign as the poorest Chandler adaptation until 1973 when Elliott Gould appeared in a shambolic rendering of The Long Goodbye. By the way, Robert Altman’s shabby duplication of Chandler deserves its low esteem. Charles Champlin described Gould’s rendering of Marlowe as "an unshaven semi-literate dimwit slob who could not locate a missing skyscraper," a criticism still apt (qtd. in Halliwell’s 449). Shane Black, another veteran scriptwriter alongside Robert Towne (Chinatown) and William Goldman, paid a curious homage (besides the title) to this ugly film in The Long Kiss Goodbye with Gina Davis and Samuel L. Jackson. There’s a television set in their hotel room playing the grocery store scene from the Altman film.

Because it’s hard to define what a "classic" is in the noir sense–especially when there are so many diverse opinions of what exactly noir is in the first place–we fans are like rat terriers who can’t formally define a rat, but we know one when we see one. Part of the difficulty lies in the excellence of the films of the forties. The directors and writers of filmed novels of Hammett, Chandler, and Cain set a high mark for later directors because they were good, and secondly, they were faithful to the moral ambiguities of the authors’ protagonists, which is not at all the same as being faithful to the text, an accomplishment of little merit in itself.

Foremost, there’s Billy Wilder, whose Double Indemnity set the pace for all afterward. Fred MacMurray’s narrating the story of his crime into the recording machine to his supervisor played by Edward G. Robinson is nothing short of brilliant. He’s no Marlowe, a knight errant of the mean streets, but a mere insurance salesman, as middle class as you can get. As he conspires with Barbara Stanwyck’s character to murder her husband for the money, he limns those dark places where noir loves to curdle in a basically good man’s brain and as he backtracks his way relentlessly from "innocence" to corruption, with the audience accompanying him, through his own demise. Six years later Wilder would go over the top in his Sunset Boulevard. The excess of Gloria Swanson’s paranoia and William Holden’s narration from beyond the grave—that is, while doing the dead man’s float, made the premier night’s audience hoot with laughter. But by then chiaroscuro and paranoia would set a standard for noir that would carry forth to this day. No surprise that Double Indemnity has been called the archetype of noir films. Writer-director Lawrence Kasdan revamped DI sans credit in his 1981 Body Heat, though the critics lambasted it. The film remains an icon.

Foremost, there’s Billy Wilder, whose Double Indemnity set the pace for all afterward. Fred MacMurray’s narrating the story of his crime into the recording machine to his supervisor played by Edward G. Robinson is nothing short of brilliant. He’s no Marlowe, a knight errant of the mean streets, but a mere insurance salesman, as middle class as you can get. As he conspires with Barbara Stanwyck’s character to murder her husband for the money, he limns those dark places where noir loves to curdle in a basically good man’s brain and as he backtracks his way relentlessly from "innocence" to corruption, with the audience accompanying him, through his own demise. Six years later Wilder would go over the top in his Sunset Boulevard. The excess of Gloria Swanson’s paranoia and William Holden’s narration from beyond the grave—that is, while doing the dead man’s float, made the premier night’s audience hoot with laughter. But by then chiaroscuro and paranoia would set a standard for noir that would carry forth to this day. No surprise that Double Indemnity has been called the archetype of noir films. Writer-director Lawrence Kasdan revamped DI sans credit in his 1981 Body Heat, though the critics lambasted it. The film remains an icon.

Jim Thompson’s After Dark, My Sweet (1955 novel; film 1990) is one of those gems that pop up in the midst the Dreck of Hollywood. At the end when punchy, brain-damaged "Kid" Collins arranges to take a bullet in the back from his female crimey, one alcoholic psycho-bitch on wheels, his interior monologues and outward actions have already shown him smarter and more humane than the others, who think they’re exploiting his mental weakness and setting him up for the double-cross. Thompson’s naturalism (that sense of foreboding and doom from nineteenth-century continental writers like Balzac and the Girancourt brothers through English writers like Thomas Hardy to Americans Stephen Crane, Frank Norris, and Theodore Dreiser) is among the bleakest and resembles those early Black Mask writers. Here’s the dying Collins, a self-sacrificial lamb, after the botched kidnapping ends in disaster:

Jim Thompson’s After Dark, My Sweet (1955 novel; film 1990) is one of those gems that pop up in the midst the Dreck of Hollywood. At the end when punchy, brain-damaged "Kid" Collins arranges to take a bullet in the back from his female crimey, one alcoholic psycho-bitch on wheels, his interior monologues and outward actions have already shown him smarter and more humane than the others, who think they’re exploiting his mental weakness and setting him up for the double-cross. Thompson’s naturalism (that sense of foreboding and doom from nineteenth-century continental writers like Balzac and the Girancourt brothers through English writers like Thomas Hardy to Americans Stephen Crane, Frank Norris, and Theodore Dreiser) is among the bleakest and resembles those early Black Mask writers. Here’s the dying Collins, a self-sacrificial lamb, after the botched kidnapping ends in disaster:

. . . I grinned, because she didn’t really mean a thing by it, you know.

I barked, I guess it sounded like a bark maybe; my body jerked, rolled a little. And then I stopped.

I just kind of stopped all over. (133)

This is closer to Cain’s sordid world of catastrophes in plotting and biased toward the depraved losers that Cornell Woolrich once favored. Thompson’s grim tale adds a noble dimension to the luckless, downtrodden Collins that shows readers a moment within his grasp when escaping his dire fate, looming ever closer, is yet possible. No self-respecting gun-barrel philosopher like Marlowe or Spade would ever put themselves into this kind of situation. For one thing, there’s a stilted prudery in the sexual regions of these early tough-guy novels that belies their own rationale about women and sex (i.e., the femmes fatale were always poised to kill you or betray you so mating was riskier than a black widow honeymoon). Today’s film noirists know no such barriers and possibly err on the side of excess in a kind of belated homage to their hamstrung predecessors who had the censors to contend with. Give Thompson his due because he had no problem portraying random sexual couplings in 1955—and, yes, the girl was going to shoot him in the back no matter what.

Thompson also wrote a pair of screenplays for Stanley Kubrick. His filmed novels include Pop. 1280 [Coup de Turchon], A Hell of a Woman [Serie Noire], The Killer inside Me and the better-known pair, The Getaway and The Grifters. It isn’t for me to elect After Dark to sleeper status, but this one grabs ever more audiences. James Foley’s effort to transplant the stink of Thompson’s familiar back alleys into chic "designer cynicism" might have failed, according to one reviewer of the Washington Post, but audiences still detect its enduring qualities beneath those California pastels and the arid landscape of Indio, California. Thompson’s rawness doesn’t translate well to film anymore than the reticence of Ross Macdonald’s lean writing and dialogue would a decade later; nonetheless, the brooding isolation of Jason Patric as Kevin "Kid" Collins and the avarice and criminality of Bruce Dern’s character, Uncle Bud, not to mention the hot-cold of Rachel Ward’s rendering of a two-timing barfly, make this turf very familiar indeed to noir fans.

Good noir films always make your skin crawl in the way that serial-killer flicks attempt to do but rarely can. Whatever happened to the aimless drifters like "Kid" Collins, knocked around by life? Today they’re all cut and buffed, belying their effeminate good looks with designer stubble, and either straddling Harleys or casual women they meet on the road. We need more films like Out of the Past with Robert Mitchum’s sleepy-eyed menace.

Good noir films always make your skin crawl in the way that serial-killer flicks attempt to do but rarely can. Whatever happened to the aimless drifters like "Kid" Collins, knocked around by life? Today they’re all cut and buffed, belying their effeminate good looks with designer stubble, and either straddling Harleys or casual women they meet on the road. We need more films like Out of the Past with Robert Mitchum’s sleepy-eyed menace.

One standard of excellence in noir films is that they never forsake brutal honesty about human failings. Their characters’ moody cynicism, which always leads to self-betrayal and seldom redemption, whether revealed in plot or dialogue, has to come from credible motives. For their times Maltese Falcon and Double Indemnity were daring in their portrayals of male leads who were not straight-arrow, likeable good guys but complex characters who combined mentality and muscle, whether for good or not-so-good. James M. Cain’s protagonists are probably less palatable for this reason because his novels lean toward Naturalism with a big N, meaning no matter what a Cain character does or plans, the world is going to mark him out for a serious clobbering.

But what troubles modern fans of noir is that many scripts are nowadays hashed out by Hollywood scriptwriters (i.e., males in their twenties with UCLA film degrees) who do not know the tradition of Hammett’s Spade or Chandler’s Marlowe well enough to understand that mere semblance to noir isn’t enough, that you (scriptwriter and filmmaker) have to include more than clipped, tough-guy talk and a lot of deep-dish cleavage to justify a character’s claim to being a legitimate son of Marlowe. I’m thinking of the 1998 Wild Things, another noir-manqué effort with frenzied double- and triple-crossing between Matt Dillon and Kevin Bacon until the last reel attempts to explain everything; in other words, just another gluttonous excursion into noir’s excesses. One can’t blame actors for the fact that there are far too many cinematic heroes like Harrison Ford in Hollywood Detective who seem to be looking for that one memorable sound byte, à la sorehead Harry Callahan, to "make their day," or blockbuster film without regard to the foundation of what makes adaptations work in noir—namely, brilliant writing and credible motivations of complex characterization.

Capturing the atmosphere in sepia tones or swapping plot reversals faster than a Sunday NFL pile-on does not a classic make. But, let’s be clear: film is film; a novel is a novel, and so forth. One can’t measure the two art forms by a single yardstick and the old cliché that a good book makes a bad film is as often as not false. As lawyers say, res ipsa loquitur—the thing speaks for itself. It’s nearly impossible to underestimate noir’s influence on the thriller. Oliver Stone’s U-Turn, David Fincher’s Se7en, and Clint Eastwood’s recent Mystic River all owe a debt to noir’s irreplaceable theme of corruption and rot at the heart of a good man or a good community. By the time the loner, the drifter, the p.i., or the cop turns up on the scene, paradise is long gone, baby.

Capturing the atmosphere in sepia tones or swapping plot reversals faster than a Sunday NFL pile-on does not a classic make. But, let’s be clear: film is film; a novel is a novel, and so forth. One can’t measure the two art forms by a single yardstick and the old cliché that a good book makes a bad film is as often as not false. As lawyers say, res ipsa loquitur—the thing speaks for itself. It’s nearly impossible to underestimate noir’s influence on the thriller. Oliver Stone’s U-Turn, David Fincher’s Se7en, and Clint Eastwood’s recent Mystic River all owe a debt to noir’s irreplaceable theme of corruption and rot at the heart of a good man or a good community. By the time the loner, the drifter, the p.i., or the cop turns up on the scene, paradise is long gone, baby.

Even if, worst case, noir is a stew, you can still spoil it with wrong ingredients. Because there isn’t a single recipe for noir’s sauce, it does seem to come down to what your tastes crave. So why is it that filmmakers seem to fumble such an easy recipe so often? For every Chinatown, there are a dozen Palmettos.

Even if, worst case, noir is a stew, you can still spoil it with wrong ingredients. Because there isn’t a single recipe for noir’s sauce, it does seem to come down to what your tastes crave. So why is it that filmmakers seem to fumble such an easy recipe so often? For every Chinatown, there are a dozen Palmettos.

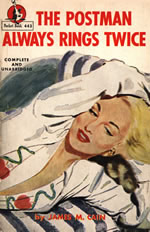

Another novel-into-film that deserves special mention is The Postman Always Rings Twice, both the 1946 John Garfield-Lana Turner version and the 1981 remake with Jack Nicholson. Noted playwright-scriptwriter David Mamet was behind the Nicholson version, and although critics did not take to its cheerless eroticism, he captured the gloomy spirit and fatalism of the Cain novel. That alone would guarantee commercial failure.

Another novel-into-film that deserves special mention is The Postman Always Rings Twice, both the 1946 John Garfield-Lana Turner version and the 1981 remake with Jack Nicholson. Noted playwright-scriptwriter David Mamet was behind the Nicholson version, and although critics did not take to its cheerless eroticism, he captured the gloomy spirit and fatalism of the Cain novel. That alone would guarantee commercial failure.

John Dahl has directed an extremely fine trio of noir films in the last decade, although none, as far as I know, is an adaptation of noir fiction. He says, "I’m fascinated by the psychology of the characters—the deceit, the betrayal, the desperation" (qtd. in "Last Seduction"). Of Red Rock West (1992), notes Derek Malcolm writing for the Guardian: "[The film expresses total] confidence in its cinematic convictions" (qtd. in Halliwell’s 621). James Ellroy has been adapted twice; his first was in loosely based on one of his early novels in which the rogue detective, played by James Woods, chases a demented woman-killer. Ellroy kept the Woods character going but split him off, psychically speaking, into sharper portraits in subsequent works. Everything after Brown’s Requiem seems to be moving toward that chiseled style and the hard boys he now favors.

We see this transition from good cop to bad cop best in the villain portrayed by James Cromwell as Dudley Smith in L.A. Confidential. Guy Pierce’s Lt. Exley is a far cry from Russell Crowe’s Bud White, but by novel’s (and film’s) end, these two battered warriors in blue are brothers in arms most literally—they share the same woman, the luscious Kim Basinger character cut to look like Veronica Lake. Ellroy’s own mean streets include a murdered mother in his youth (subject of his recent autobiography), a Los Angeles background of addictive and disorderly behavior, window-peeping voyeurism and panty-sniffing burglaries, one such escapade landing him in an L.A. caboose for several months. He may be the finest noir stylist writing in America. He has created out of the formulaic and predictable staples of hardboiled crime-writing fiction a style that one must call unique right down to those staccato-burst sentences of his that evolved after White Jazz.

We see this transition from good cop to bad cop best in the villain portrayed by James Cromwell as Dudley Smith in L.A. Confidential. Guy Pierce’s Lt. Exley is a far cry from Russell Crowe’s Bud White, but by novel’s (and film’s) end, these two battered warriors in blue are brothers in arms most literally—they share the same woman, the luscious Kim Basinger character cut to look like Veronica Lake. Ellroy’s own mean streets include a murdered mother in his youth (subject of his recent autobiography), a Los Angeles background of addictive and disorderly behavior, window-peeping voyeurism and panty-sniffing burglaries, one such escapade landing him in an L.A. caboose for several months. He may be the finest noir stylist writing in America. He has created out of the formulaic and predictable staples of hardboiled crime-writing fiction a style that one must call unique right down to those staccato-burst sentences of his that evolved after White Jazz.

The early adaptations of Chandler were, by and large, faithful to the credo of the lone hero (Marlowe) as well as to Chandler’s beliefs in what good "mysteries" must have to succeed. He enumerated these succinctly as credibly motivation of character and story line; technical soundness; and realism as to character, setting and atmosphere. Chandler’s most important criteria, however, were these precepts so often flouted today: one (i.e., mystery or film) must not try to do everything at once and one must punish the criminal, not necessarily via the courts (qtd. in Kahn x-xi). It is an important distinction to read into the subject for the verbs do and punish of that last sentence an agency beyond the mystery itself or the filmmaker; we have to feel this kind of justice to be right deep in our bones or it’s strictly another cheap deus ex machina of the made-for-TV variety.

Ten years ago journalist Douglas Coupland wrote a scintillating essay about the scene of the notorious Nicole Brown Simpson/Ron Goldman murders. He dissects Brentwood, California as a paradoxical place where evil should never have happened and yet was the perfect place for it. An übersuburb of Los Angeles, Brentwood is an unreal "city" right to its faux Hollywoodian core. It is a lost paradise, a failed utopia, and a nirvana for these neurotic denizens of its plexiglass condos and where shrinks outnumber cops. As New York Times film critic Pauline Kael once wrote: it’s the "celebration of rot" that noir is that makes these dark films more than a trendy revival of the forties novels and Los Angeles ambience. Beneath the "entertainment" lies a cry of warning. When a pampered community of citizens achieves its "secular nirvana," as Coupland refers to the goal of today’s Brentwoodians, trouble, randomness, disorder, and entropy await, for the props are about to crumble beneath the monster houses and manicured lawns with their exotic landscapes. People without "place" or a sense of history lose their bearings, then culture ceases to give us what we need to forge our identities—namely, religion, family, ideology geography, politics, and most important, avers Coupland, "a sense of living within a historic continuum" (25). Without that, we lose our identities, become victims of randomness, and experience a de facto sense of being, to borrow Coupland’s coinage, "denarrated." Nicole Brown Simpson’s bloody death was an affront to this "well maintained" community that goes to extreme lengths to hide its infrastructure and its psychic blemishes. How ironic that Marilyn Monroe’s house at 12305 Fifth Helena was just a stone toss from the house where Raymond Chandler wrote his raw tales of the vice-riddled Gomorrah of Los Angeles, a city without borders and endless suburban sprawl, or to borrow an Ellroy title, The Big Nowhere.

It is also the key to an understanding of the reason why few modern films fail to capture the essence of noir. There are successes, to be sure, like Joel and Ethan Coen’s Blood Simple (1983), which like so many owes more than a little to the Hammett-Cain-Chandler tradition. It isn’t about mere atmosphere and a backstabbing plot laced with infidelity, nor much less does it concern those de rigeur eye-popping interludes of frenzied violence films feel they owe their audiences; these are as out of place in noir as pornography in a Bollywood production. Noir must reveal the secret fear we all have that our own communities are rotten with a moral cancer. That those closest to us are going to betray us. It is akin to that recurring dream where the face of our friend outside the window suddenly leers and transforms itself into the face of evil. We know in a singular moment that we have been deceived by a reality that is not at all what we expected. Chandler’s Marlowe lives in this dark region of the mind without losing his moral compass; the same goes for Lew Archer in Southern California.

Ellroy’s maverick hero big Pete Bondurant is a slightly edgier and different breed of cat, however. The ex-L.A. County deputy sheriff knows where the lines are drawn as he prowls among the detritus of broken dreams amid the murderous liaisons that populate his dangerous world. America awakened to the corrupt politics of the rabbit-faced Kennedy clan from the mobbed-up old man through Bobby and Jack, whose penile probe must have had a callous at the tip from the many sexual rendezvous of his Camelot days. CIA, FBI, and a trio of mafia capos from New Orleans, Florida, and Chicago named Carlos, Santo, and Momo link arms to deal a fatal blow to the nation’s optimism on that brain-spattered day in Dallas. A time of bad juju, as Pete says at the beginning of his narration in American Tabloid. Bondurant is a déclassé cop and part-time hood, several notches below Jake Geddes of Chinatown. Jake’s savvy for self-preservation amid the internally rotten politics of the desert community Los Angeles once was is a suaver version of Pete’s cunning against similar forces of darkness in his wanderings between the coasts. It’s a skewed but unbroken line from the modern-day Bondurant back to Jake Geddes, however.

One can’t forget the brilliant writing and directing of John Huston in the 1941 remake of the Maltese Falcon; it’s as if everything is intact in the Polanski film, both a homage and a tour-de-force in which everything succeeds. (Huston’s own more-than-cameo role in the 1974 noir classic was a fine tribute and choice by director Polanski, that flamboyant exiled child-rapist with his own demons.) Whereas Jake is hauled away from the scene of carnage (i.e., the dead Evelyn Mulwray) by his associates, Pete will survive the coup d’etat, the bad guys, and find new ones out to con or kill him in The Cold Six Thousand (Vintage, 2001).

Noir opens the door to new realities. As the great tragedians of Greece knew so profoundly well, this is needed to restore the moral order of the universe to equilibrium. To live with blinders on, as we did in the Camelot era, and as we are doing now in a more dangerous time where we see a triumvirate of forces acting in collusion—call it the media-politico-religio autocracy, if that isn’t too pretentious—and you have fertile ground for the next generation of noirists. That is quite an obligation for such a bratty tyke as noir happens to be in the long, semi-respectable history of the mystery novel with its confirming and unchallenging tradition of mainstream whodunits, cozies, locked-room puzzles, etc.—all those atrocious and trashy books and films that eschew violence, show grannies cracking international dope-cartel conspiracies and so forth—at least Paul Newman’s version of the detective-in-his-dotage reminds one of a better tradition. Au contraire, reading or watching noir is not escapism; it is, I firmly believe, elucidation, confirmation of malevolence, and a genuine, whole-hearted reveling in the metaphysics of being.

Modern noir films show the private eye in a range of guises, sometimes as a moral family man (Nicholas Cage in Eight Millimeter), sometimes as a freewheeling, sexual libertine (Michael Harris in The Soft Kill), as victim and dupe of women (Woody Harrelson in Palmetto). Cage is a victim of schemers but not only is he not a libertine in 8 MM but he is a solid, yard-raking citizen of the middle classes struggling with bills and worried about his infant daughter’s college money. Harrelson is a sexual alley cat in Palmetto, which trait makes it easy for him to be duped by a pair of women. The Soft Kill, the weakest of the bunch, violates every point Chandler had tried to make about a mystery’s need to be "realistic" and true to a character’s motivations; it is lost in this muddled collection of noir clichés. But it proves how easy it is to package a hollow facsimile of the hardboiled crime thriller today. Lawyer-novelists all know that the law in action is one boring, dull-as-dishwater phenomenon, so Turow, Scottoline, Grisham et alia write their novels with as little actual courtroom drama as possible.

Modern-day television variations of the lone-wolf crime solver are, if anything, worse when it comes to portraying reality and crime. For one thing, they sanitize the human passions right out of it. The protagonists of the CSI programs are interchangeable and show the same slick veneer of cop work; in other words, no drudgery permissible to wear out the audience’s short attention span. Keep the glitz of computer-generated technology moving rapidly in bright colors, add a wisecrack or naughty double-entendre every so often lest the technical jargon impinge on the viewer’s patience, and you have Sherlock Holmes variously recast as William Peterson, Gary Sinise, or their red-haired Miami counterpart. They can deduce a litany of information about the killer right on the spot by looking at a speck of dirt or a holding a strand of hair or fiber in a pair of tweezers and tell us the height, weight, sexual proclivities, and reading habits of the killer within a sixty-minute episode (sans the eighteen minutes of commercial time) with portions devoted to gaping through some gee-whiz 3-D machine that plunges the reader along on a microbe-sized ride deep into corpses’ red and sloshy organs. A diet of these fantasy dramas and their opposites—those idiotic reality shows—have reduced American viewing tastes to the level of ass-scratching losers who truly believe detectives never have to write a field report or never missed an important phone call or contact, never have to follow a prescribed routine like any working-class stiff, or ever wait for the same lowlife deadasses to stop lying to them in interrogation rooms. (Actually, as we know, it’s the bad guys and the cops who do the lying in interrogations. Ever heard some mope on Cops ask a vice cop, "If you’re a cop you have to tell me." Oh yeah, says who, my man?) I may as well digress further to the second Bad Boys film with Martin Lawrence and Will Smith for a moment. Their antics remind me how far past the believable scripts have gone today (detectives choose their own cases, draw and shoot service weapons on a daily basis, get into fights, come and go as they please, and never answer to a higher authority except a boss who, deep down, really admires and respects their maverick ways of solving hard cases). In the midst of this television and film miasma of machismo and pyrotechnics somehow manages to glisten the occasional sparkle of a noir gem.

Noir affirms the epistemology of the angry loner; it thrills to the root of our ontological self and need for "stories." It asks us to believe in heroism in an age of shrill feminism and uncertainty about masculinity, and what it means to be a man unaffiliated with a soul-killing corporation. We live in a time when mediocrity prevails everywhere; corruption is so widespread from top to bottom that we shuffle along in our ordinary boring lives inured to the next news item about yet another glamorous scoundrel who lies, steals, or betrays the public trust. Now and then, however, we lose our complacency and then life gets interesting. Think of all those fat or sleek tourists basking on chaise lounges before the waves rolled them away to a horrible death in the Christmas tsunami of 2004. Violence restores our vision and reminds us that God is not in His heaven and, by God, all is not right with the world. (One whey-faced teenager affirmed that her survival was a miraculous "test," as if God’s annihilation of 160,000 human beings was designed for this singular purpose.)

That’s why privates who love to wisecrack annoy me so much. Give me a laconic, humorless detective like Houston’s David L. Lindsey’s Stuart Haydon over the inane Kinky Friedman models. Detroit’s Elmore Leonard (the Leonard after Get Shorty) has lost his touch; the dry wit and clever plotting of his early books is gone. The former writer of cowboy novels (albeit with a noir flair) and scriptwriter for B-grade westerns now favors wisecracking black urban thugs as the best examples of stylishly hip malevolence. Tough-guy heroes like Ellroy’s Bud White and Pete Bondurant are throwbacks to the Continental Op, Sam Spade, Philip Marlowe, and Lew Archer. But black-edged humor isn’t everyone’s cup of tea, I grant you. Murder of a small-town nobody or an American president; conspiracies, mayhem, and political intrigue; rapes and mutilations; deaths of innocents; deceits galore; cruel treacheries by our lovers, our partners, and our family members—not the stuff of children’s games. But these are the ingredients of life on this wretched planet for the majority of us who keep our eyes open. If you want comedy, find a comedy club, but please get out of the noir business, whether as fan or writer or filmmaker. It is a dish reserved for heartier, saner palates, those which disdain the saccharine.

###

Copyright © 2005 Terry White

References

After Dark, My Sweet. Dir. James Foley. Perf. Jason Patric, Rachel Ward, and Bruce Dern. Artisan, 1990.

Chinatown. Dir. Roman Polanski. Writ. Robert Towne. Perf. Jack Nicholson, Faye Dunaway, and John Huston. Paramount, 1974.

Coupland, Douglas. "Los Angeles 90049." The New Republic 19 Dec 1994: 18-25.

Double Indemnity. Dir. Billy Wilder. Writ. Billy Wilder and Raymond Chandler. Perf. Fred McMurray, Barbara Stanwyck, Edward G. Robinson. Paramount, 1944.

8MM. Dir. Joel Schumacher. Writ. Andrew Kevin Walker. Perf. Nicolas Cage, James Gandolfini, Peter Stormare, and Anthony Heald. Columbia, 1999.

Halliwell’s Film & Video Guide. Ed. John Walker. New York: HarperCollins, 1997.

Hinson, Hal. "After Dark, My Sweet." Washington Post 24 Aug 1990 18 Jan. 2005 http://www.washingtonpost.com.

Kahn, Joan. Intro. The Midnight Raymond Chandler. Boston: Houghton, 1971.

L.A. Confidential. Dir. Brian Hanson. Writ. Brian Helgeland. Perf. Russell Crowe, Kim Basinger, Guy Pierce, and Kevin Spacey. Regency-Warner, 1997.

The Last Seduction. Dir. John Dahl. Writ. Steve Barancik. Perf. Linda Fiorentino. William Pullman, and Peter Berg. ITC, 1994. Dahl’s quote above comes from a Main Art Theatre flyer. Royal Oak, MI. 1994.

Out of the Past. Dir. Jacques Tourneur. Writ. Geoffrey Homes. Perf. Robert Mitchum, Jane Greer, Kirk Douglas, and Rhonda Fleming. RKO, 1947.

Palmetto. Dir. Volker Schlörndorff. Writ. E. Max Frye. Story by James Hadley Chase. Perf. Woody Harrelson, Elisabeth Shue, and Gina Gershon.

Red Rock West. Dir. John Dahl. Nicholas Cage, Lara Flynn Boyle, and Dennis Hopper. DeLuxe, 1992.

The Soft Kill. Dir. Eli Cohen. Writ. Alex Kustanovich. Perf. Michael Harris, Brion James, Carrie-Anne Moss. Dream Entertainment, 1994.

Sunset Boulvevard. Dir. Billy Wilder. Writ. Charles Brackett and Billy Wilder. Perf. Gloria Swanson, William Holden, and Erich von Stroheim. Paramount, 1950.

Thompson, Jim. After Dark, My Sweet. New York: Vintage-Black Lizard, 1990.

Read an extract from Terry White's Strawberry Girls

TERRY WHITE is an associate professor at a regional campus of Kent State University in Ashtabula, Ohio, where he was born and raised. He is married to Judy and has three children, his best creative work to date. He has two hardboiled characters: a Chinese-American FBI agent named Annie Cheng and a drunken existentialist P. I. named Thomas Haftmann. Haftmann's most recent appearance is in the March issue of Hardboiled.

Contact Terry