- Welcome

- Noir Zine

- Allan Guthrie

- Books

"...those who enjoy the darker side of the genre are in for some serious thrills with this..."

Laura Wilson, The Guardian

Published in the UK by Polygon (March 19th, '09) and in the US by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (Nov '09).

carny noir: bearded ladies and a man-eating chicken

by Michael S. Chong

You don’t hafta knock’em off. Tip’em flat. Four flat gets you choice. One win’s all it takes. Biggest per-rizes on the midway. Who’s uh next a heah?! You pay your money you take your chances.

I still remember my spiel from my carny summer jobs as a teen. For a few summers at the annual Canadian National Exhibition in Toronto, I worked a softball pitch game called Tip’Em Over.

One of my old bosses taught me to wear a couple of rings on my hands. As I held a softball in front of the mark’s face, the glitter off of the rings would catch their eyes, and like some animals, they would be momentarily hypnotized by the flash. An aid to the sell. Do it well enough and you could tip your joint, or hold a crowd, lining up for a chance to lose their money.

Carnies aren’t conmen. Carnies have to make their marks like it. Make them feel like their loss was due to their own incompetence and not to a game rigged to only rarely pay out. Tell them "You were so close that last time. You’re just getting warmed up. You’re due. You deserve one of these big prizes. Look, I like you, you’ve spent some money here, I’ll cut you a deal..." while they spend twenty times what the actual cost of the prize was and still walk away with nothing. It’s not easy.

Con men can take the money and just disappear. Be it the short or long con, they can just fade. Carnies have to do the same thing the next night, maybe in a different town, but the gig is the same. They travel like gypsies, set up stakes in a new town and let the marks come to them.

Carnivals in noir may be perceived as self-contained organized crime. A cynical view of American society and the American dream where there’s entertaining distractions in amusement rides and side shows; gambling for money and stuffed prizes; sex and lust in the hootchie cootchie model posing shows; and food in the form of hotdogs, hamburgers and all things deep-fried. Even a little education in the pickled punk shows. What else does modern man expect from society? From our fast-food culture which seeks to entertain us to death with the freaks of celebrity tabloids, reality TV and Internet porn.

In noir, carnies that commit crime are trying to pull a fast one on those that earn a living doing the same. Doing something illegal in a carnival is like jaywalking when every vehicle runs red lights. Dangerous but admirable if you succeed.

Robert Edmond Alter writes in Carny Kill (1966), a murder thriller set in a carnival, about how Hollywood has used carnivals as a similar, but less dark symbol:

"Well--you remember how an everyday slicker like Tyrone Power, say, would meet a poor little rich girl like Loretta Young, and how in one night he would show her the real and the entire soul and spirit of America, which was always exemplified by Coney Island?" p. 67

Hunter S. Thompson in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1971) saw the American Dream in microcosm in the carnival-like Circus-Circus casino:

"The Circus-Circus is what the whole hep world would be doing on Saturday night if the Nazis had won the war. This is the Sixth Reich. The ground floor is full of gambling tables, like all the other casinos... but the place is about four stories high, in the style of a circus tent, and all manner of strange County-Fair/Polish carnival madness is going on up in this space...

The madness goes on and on, but nobody seems to notice. The gambling action runs twenty-four hours a day on the main floor, and the circus never ends. Meanwhile, on all the upstairs balconies, the customers are being hustled by every conceivable kind of bizarre shuck. All kinds of funhouse-type booths. Shoot the pasties off the nipples of a ten-foot bulldyke and win a cotton-candy goat. Stand in front of this fantastic machine, my friend, and for just 99 cents your likeness will appear, two hundred feet tall, on a screen above downtown Las Vegas. Ninety-nine cents more for a voice message. Say whatever you want fella. They’ll hear you, don’t worry about that. Remember you’ll be two hundred feet tall." p. 46-7

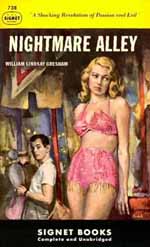

The traveling carnival comes into a town and changes the area into another world. William Lindsay Gresham wrote about this transformation in Nightmare Alley (1946). It is hard to believe that Gresham got all his carny knowledge second-hand since his story of Stanton Carlisle, a carny who tries to make his way into the big-time mentalist/spiritualist con, but falls back down, reads like it was written by someone who has travelled:

The traveling carnival comes into a town and changes the area into another world. William Lindsay Gresham wrote about this transformation in Nightmare Alley (1946). It is hard to believe that Gresham got all his carny knowledge second-hand since his story of Stanton Carlisle, a carny who tries to make his way into the big-time mentalist/spiritualist con, but falls back down, reads like it was written by someone who has travelled:

"Dust when it was dry. Mud when it was rainy. Swearing, steaming, sweating, scheming, bribing, bellowing, cheating, the carny went its way. It came like a pillar of fire by night, bringing excitement and new things into the drowsy towns -- lights and noise and the chance to win an Indian blanket, to ride on the ferris wheel, to see the wild man who fondles those rep-tiles [sic] as a mother would fondle her babes. Then it vanished in the night, leaving the trodden grass of the field and the debris of popcorn boxes and rusting tin ice-cream spoons to show where it had been." p. 557-58

Joe R. Lansdale's crime novel Freezer Burn (1999) tells the story of a loser who screws up a firecracker stand robbery, gets horribly stung by mosquitos during his escape, joins a sideshow after being mistaken for a freak,then gets sucked into a femme fatale after he heals into a James Dean lookalike. In it, Lansdale depicts the setting up of a portable community:

"They parked the trucks and cars and trailers in a field just inside of town. Some of the trailers had sides that opened up and they opened them and propped them so that they might serve as counters for selling hot dogs and pretzels and all manner of junk. They put together little frames with curtains on them and set them about the field and stuffed them full of pins to knock down and hoops and buckets and jars to toss pennies or balls into, arranged stuffed animals all about, the cheap sort with eyes children could peel off and swallow.

They put up some large tents and a couple of fitted grandstands where you could sit, and they brought out and put together a few rides, the tiltawhirl being prominent, but the guy who owned and operated it called it a whirligig and so everyone else did. It was old and rusty with badly painted metal bucket seats. The paint was green, but time had taken a toll on it. When the wind blew, the bolts that held it together - and it was missing a few - rattled and the whirligig buckets swung slightly and the whole thing creaked and made you think of bodies with shards of metal poking through them. The guy who ran it looked like an ex-con and was. He was the second oiliest man in the carnival. Only a fellow worked there with two teeth was nastier looking. A guy called Potty, which was what was suspected of being under his fingernails." p. 67-8

Once the midway is alive, the carnies need to draw in the marks by any means necessary. Fredric Brown, who worked as a carny, writes authentically about carnivals in his two books Madball (1953), a noir with chapters alternating perspectives from various carnies, concerning the takings from a bank heist causing murders on the midway, and The Dead Ringer (1948), the second in his series of books with Ed Hunter and his uncle Ambrose, this time working in a carnival where a midget, a chimp and a boy are found killed in and around the carnival but in different towns.

In Madball, in which the murderer’s view is depicted early on without giving their identity away, Brown writes about the sounds and atmosphere one experiences entering the midway:

"It needed music, that walk down the bright midway, "Hail the Conquering Hero Comes." The merry-go-round was playing "Dardanella" instead, but that didn’t matter really. The music Mack Irby heard wasn’t the merry-go-round’s organ nor the three-piece combo of the jig show; it was the overall sound of the carnival on a busy night, voices and laughter and the strident selling spieling grinding over p.a. systems and the crack of rifles in the shooting gallery and singing yelling shuffling, the thud of baseballs and the soft ratchets of fortune wheels and the basedrum call to bally, try your luck, mister, pitch till you win, the big show just about to start, a few seats left, three balls for a dime, see the strangest people on earth, win a kewpie doll for the little woman, get ‘em while they’re hot, pick your lucky number, and inside the little lady will show you, hurry, hurry, win an Armour ham, see the alligator boy, this is the show you came to see, naked and unadorned, every number wins a prize, the show’s about to start, step right up and try your luck..." p.7

In The Dead Ringer Brown, through the voice of Ed Hunter, describes how entering a carnival is like encountering an unearthly organism:

"I stood there at the curb outside, looking at the big entrance gate, big and bright and gay like the gates of Paradise, that was set back forty feet or so from the street. Through it and around it I could see the tops and the midway; I could hear the screech of the Whip, the thump of the bass drum call to bally, and the thousand voices blending into one big voice, a voice of the crowd and the carney mixed, all one strange sound. It was as though I’d never seen a carney lot before, or heard that sound." P.36-7

And this is coming from a character who was a carny. The unreality of the midway caught me a few times. I’m sure the travellers were already jaded to the lights and noise. All it was to them was their working environment. They ate, breathed and slept around it. This was their community. This was their home. They even have their own code and language. There were a couple of guys I never could understand.

Gresham wrote about the carny language. A hybrid of many:

"Stan had never been this far south and something in the air made him uneasy. This was dark and bloody land where hidden war traveled like a million earthworms under the sod. The speech fascinated him. His ear caught the rhythm of it and he noted their idioms and worked some of them into his patter. He had found the reason behind the peculiar, drawling language of the old carny hands - it was a composite of all the sprawling regions of the country. A language which sounded Southern to Southerners, Western to Westerners. It was the talk of the soil and its drawl covered the agility of the brains that poured it out. It was a soothing, illiterate, earthy language." p. 585

The carnies I worked with all spoke a little funny. Less when they were having conversations, but a true colloquial accent came out when they were spieling. At the time I thought this was due to the variety of backgrounds I encountered amongst the travellers. They were from all over. Eastcoasters, southern Americans, native Indians and more than a few ex-cons. There were generations of carny families who had been in the game since the forties. I even met a family who had worked the carnival at the old Toronto pier from the twenties. There were also the runaways. You know like how kids used to runaway with the circus. One kid who worked as my ball boy, setting up the milk cans and retrieving thrown balls, was like ten, but acted like he was eighteen, smoking, drinking and swearing. He had been taken in by a childless couple and told me he had been away from home for the last couple of years. I always took the stories of travellers as embellished or full-out fabrications. They weren’t all liars, but they wouldn’t let the truth get in the way of a good story.

Harry Crews wrote a non-fiction piece Carny (1979) on some time he spent with a carnival. He describes the sense of community:

"Above everything else, the carny world is a self-contained society with its own social order and its taboos and morality. At the heart of the morality is the imperative against telling outsiders the secrets of the carnival. Actually it goes beyond that. There is an imperative against telling outsiders the truth about anything." p.165

It’s a real us vs. them view. I myself was a local or what Crews describes as a first-of-May, or a short-time carny, and I felt some of that resentment to non-carnies and outsiders:

"Carnies have nothing but a deep, abiding contempt for marks and what they think of as the straight world, and nowhere is that contempt more vividly expressed than in the Tattooed Man’s response when I asked him why he had the eye put in there.

"Making them bastards pay two dollars to look up my asshole gives me more real pleasure than anything else I’ve ever done." p.168

Whenever one had a problem with the outside, they all had a problem. When a mark gets angry and aggressive, the carny "watchers" that stand amidst the game tops have special calls to bring together nearby carnies for protection. This is a code Gresham writes about:

"A carny’s a carny and when one of us is jammed up we got to stick together."

I remember after losing quite a bit of money, a large Korean man started to roll up his sleeves and began taking a few angry steps towards me, before my boss and a couple of other carnies came in and broke it up. Or should I say saved me from a beating...

Russell James’s Count Me Out (1996), a crime novel about a fighter who joins a carnival boxing booth to avoid the backlash caused by his brother who has disappeared after pulling a heist, relates the communal aspect of carnies:

"All Jet wanted was to stay here with the fair and to bury himself in its world. Inside his caravan in the corner of the fairground he was away from that exterior world -- from townies and their burdensome possessions -- from stolen money and the law....

Show people had become his family; tonight had made that clear - their unity against the townies, and the way that, despite the fracas, they had found time to tell each other about the missing Stella and had shown him that they wanted to help. Travelling people bonded, had more empathy with each other than outsiders knew." p. 297

In Carny Kill, Alter puts the relationship to marks and the outside world into more commercial terms:

"Like most carny folk I don't like people as people but only as marks. Somebody you can trim for a dime or a buck or a bundle. If you break them down and feed them to me one by one, then maybe there will be a few I will like as individuals. But not when they flow past you like bawling cattle. Who needs a stampede?" p. 18

The subculture of carnies and their view of marks as almost inhuman is revealed by Brown writing in The Dead Ringer how carnies are not supposed to enter the model show where pretty girls pose in next to nothing, the skin they expose dependent upon the local mores, laws and what they can get away with:

"What I mean is, if you’re a carney you stay out of the posing show. The models don’t mind posing in practically nothing at all for the marks, the suckers. They don’t count; they’re outsiders; you might almost say they aren’t human beings. It’s strictly impersonal. But it would be indecent for someone who knows them to go in and watch. It’d be as much Peeping Tom stuff as looking in trailer windows or over hotel-room transoms." p.40

This fellowship of carnies is reinforced by the way they are perceived and treated by the outside world. The marks in Horace McCoy’s short story The Girl in the Grave (1945) are voyeurs of a different sort and show no respect for the carnies either:

"She was buried alive, twenty feet under the ground. It cost a dime, ten cents, the tenth of a dollar, to go in and talk to her through a periscope. She had been buried for two hundred hours, which was only fifty hours short of the record; and she was the hottest thing on the Midway. We were beating customers off with sticks...

(We had a piece of thick glass down near the bottom of the periscope. It used to all be open, but a lot of wise guys would drop things down it or would spit down it and Gloria raised so much hell we had to put the glass in there to act as a screen.)" p.302

In the story’s end, it seems that the carnies have become the marks. An unattractive man has seduced the woman out of her hole with just his voice.

Usually the manipulation is the other way. When crimes occur in the carnival, it is difficult for the police to get any information or find any witnesses. Cooperation is unacceptable betrayal. Alter writes about this in Carny Kill:

"As a rule carny people never show any interest in a crime that happens in their backyard. They become deaf and dumb. They pointedly keep their noses out of it and volunteer nothing. It's the law's worry, not theirs." p. 33

Why would a carny snitch on another? The law and the carny just don’t go together. In Brown’s The Dead Ringer, a detective investigating murders connected to the carnival and Ed Hunter discuss the desire for vice and the moderating effects of law on the carnival:

"Look, think it over; what a carney would be like if the law let it run wide open, if nobody gave a damn. Your penny-pitch games that slide along the borderline of gambling would be shell games and three-card montes - and all of ‘em either as crooked as hell or with the odds so stacked against the sucker you might as well take his money with a gun. Your cooch shows would be strips, and with little tents pitched in back for customers who really wanted to lay it on the line after the-"

"Who," I said, "gave you the idea carney girls are whores? They aren’t."

"Because the law doesn’t let-" He stopped. "Wait, don’t look at me like that. I don’t mean the same girls, the ones you got now, would do that. Not all of ‘em, anyway. I mean the carney would hire broads who would put out.

"And your candy floss booth’d sell reefers instead of air, and your side shows - Oh, hell, skip it."

"If a carney peddles stuff the law doesn’t like, it’s because the mooches want it, isn’t it? Your citizens?"

He sighed. "Ed, if the majority of my citizens wanted gambling and indecency, the town would have it. Nobody’d have to go to the carney for it." p.16-7

Sounds like Amsterdam...

Every year some local news programme airs an expose of how midway games are rigged. Every game I ever worked on was winnable, despite how slim and possibly infinitesimal the odds. To win a stuffed animal the size of a small compact car, all you had to do was tip flat four stacked metal "milk bottles" weighing one kilogram each. I could only do it, maybe, once in fifteen throws and that was with a few hundred practice throws. You see we weren’t supposed to play this specific game when the marks were around. An unsuccessful demonstration would scare them away. However, one summer I worked across from one of those ring-toss-onto-the-neck-of-a-coke-bottle games and I never saw anyone win. I’m sure people won and I remember them giving prizes away, but I never saw anyone get a ring on.

Later in The Dead Ringer, when Ed Hunter is walking through the midway, he admits to himself that some games are rip-offs, but others provide fun plus a little ego boost:

"I found myself thinking about the copper, Armin Weiss, and his cracks about the carney. Down inside of me, they rankled.

I looked over the concessions as I walked by them. On plenty of them, he was pretty near right. Like the shooting game I was passing. Spud Reynolds charged two bits for three shots - at fairly short range - with a twenty-two rifle at a card with a red diamond printed on it. If you shot all the red diamond out of the card, you got a prize. A big one, your choice of a lot of flashy stuff he had hanging around. But nobody had won a prize by shooting all the red out of the card. It was theoretically possible maybe, but just not practical. It looked easy - that was the gimmick - but the best marksman in the country would have to have God sitting in his lap to do it.

I had to give Weiss that one. And plenty of the others: the game where you tried to pitch your coin so it stayed in a floating dish, the cork-guns with which you tried to knock a pack of cigarettes off a rack, the disk game. They were all pretty heavily loaded against the sucker.

But our own game wasn’t so bad. For one thing, we didn’t offer expensive flash that the mark couldn’t win. About one out of twenty-five could knock all three bottles off the box with the three baseballs and win a kewpie doll that cost us fourteen cents, sure.

But what the hell, he was paying his dime for the fun of trying, the fun of showing off in front of his girl or the other fellows, the physical fun of whaling those three baseballs as hard and straight as he could. The damn kewpie doll didn’t mean anything to him, except as a symbol, so it wasn’t really a gambling game. And there was skill involved, even if you had to have some luck besides the skill." p.25-6

Just like my old game. Things haven’t changed that much; the shooting game with the red star Brown describes in 1948 still exists today.

The only thing I liked better than taking a mark for a lot of money (I was working on points or a percentage commission of 10 per cent), was giving away a prize. Pulling down one of those huge stuffed toys and chucking it high in the air to the winner standing far back into the crowds, as far as I prompted him to create the biggest spectacle and thereby draw more marks, and yelling "There goes anothah one!" That, as they say, was the shit. Fredric Brown, through Ed Hunter, talks about this specialness:

"A carney, I thought, is a lot like a violin. It’s made up of things as unromantic as horses’ hair and sheep’s guts, and Weiss was right; it’s pitched to appeal to the nasty instincts of the public, the lust and morbid curiosity and avariciousness - but it adds up to magic, too. There’s something there that’s more than neon and gambling wheels and flesh and misshapen freakishness and - hell, I can’t explain it, but it’s there." p.168

Not exactly a crime fiction writer but one who writes from a dark place, Flannery O’Connor, in her story Parker’s Back, shows how carnivals may alter your life perspective:

"Parker was fourteen when he saw a man in a fair, tattooed from head to foot. Except for his loins which were girded with a panther hide, the man’s skin was patterned in what seemed from Parker’s distance - he was near the back of the tent, standing on a bench - a single intricate design of color. The man, who was small and sturdy, moved about on the platform, flexing his muscles so the arabesque of men and beasts and flowers on his skin appeared to have a subtle motion of its own. Parker was filled with emotion, lifted up as some people are when the flag passes. He was the boy whose mouth habitually hung open. He was heavy and earnest, as ordinary as a loaf of bread. When the show was over, he remained standing on the bench, staring where the tattooed man had been, until the tent was almost empty.

Parker had never before felt the least motion of wonder in himself. Until he saw the man at the fair, it did not enter his head that there was anything out of the ordinary about the fact that he existed. Even then it had not entered his head, but a peculiar unease settled in him. It was as if a blind boy had been turned so gently in a different direction that he did not know his destination had been changed." p.312-3

I probably wanted to become a carny after one of my countless childhood visits to the midway. The carnies looked like they had fun. The best job in the world. Sometimes it still seems that way. Even after a few summers of losing my voice from spieling and having a diet that consisted of corndogs, it still seems that way.

Sideshows were pretty much dead during my time as a carny. There were some when I was younger. One of my favourites was the Giant Man Eating Chicken. On the canvas flat on the side of a tent top, there was a hand-painted caricature of a massive white chicken with a doll-sized man clutched in one claw being fed towards its open beak. Inside, after shoving two tickets at the indifferent carny outside, I walked into the half-darkness to see a tall man eating chicken. He looked like he was over 6 feet tall, but I can’t be sure, he was sitting down. It was worth the two tickets for the laugh at the situation and myself.

The real world does that. It makes promises and doesn’t deliver. In the carnival, somehow, it’s done with charm, charisma and finesse and we, the marks, don’t seem to mind so much.

Works Cited

Robert Edmond Alter’s Carny Kill. Berkeley: Black Lizard Books, 1986. (First published 1966)

Fredric Brown’s The Dead Ringer. New York: Bantam Books, 1954. (First published 1948)

Fredric Brown’s Madball. Greenwich: Gold Medal Books (Fawcett Publications), 1961. (First published 1953)

Harry Crews' "Carny" in Blood and Grits. New York: Harper & Row, 1979. (First published in Playboy)

Russell James’s Count Me Out. London. Serpent's Tail, 1996.

William Lindsay Gresham’s Nightmare Alley in Crime Novels: American Noir of the 1930s and 40s. New York: The Library of America, 1997. (First published 1946)

Joe R. Lansdale’s Freezer Burn. London: Indigo, 1999.

Horace McCoy’s "The Girl in the Grave" in Half-A-Hundred: Tales by Great American Writers. Philadelphia: The Blakiston Company, 1945.

Flannery O’Connor’s "Parker’s Back" in Great Esquire Fiction: The Finest Stories from the First Fifty Years. New York: Penguin, 1983. (First published in Esquire April 1965)

Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. New York: Popular Library, 1971.

Copyright© 2003 Michael S. Chong

***

MICHAEL S. CHONG was born a Scorpio in the Year of the Dog. He still plays carnival games, but less for the prizes than for the spiel. Currently he feeds pigeons in The Hague, inbetween writing for nonprofit. The money's no good, but the birds and words make great companions.

Contact Michael