Author of seventeen books and more articles and short stories than there are

days in the year, James McKimmey is one of the most gifted crime writers of the '50s and '60s. Cornered, 24 Hours To Kill, Run If You're

Guilty, Squeeze Play - you'll only be disappointed if you don't like

fast-paced plots, snappy dialogue, fleshed-out characters or enough tension to

snap a bungee cord. Allan Guthrie was lucky enough to speak to James (pictured) for Noir Originals.

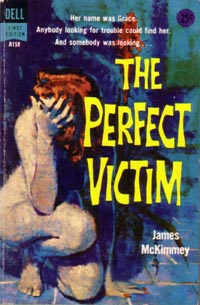

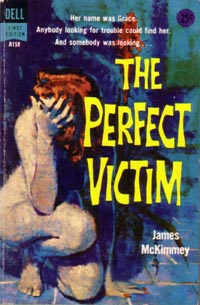

Allan Guthrie: In 1957 Cosmopolitan published a shortened version

of your first novel under the title Riot At Willow Creek. In 1958 Dell

published the longer version as The Perfect Victim. How on earth did you

manage to sell a first book so successfully?

Allan Guthrie: In 1957 Cosmopolitan published a shortened version

of your first novel under the title Riot At Willow Creek. In 1958 Dell

published the longer version as The Perfect Victim. How on earth did you

manage to sell a first book so successfully?

James McKimmey: When I was in the Army

during WWII, I had a good friend named Herb. We stayed together from Fort

Leavenworth, Kansas, all the way to Germany where he was killed in action. Herb

was a very wise young man. His advice to me about finding success was,

"Surround yourself with good people."

I’ve had two marriages in my long

life, the first to Marty for 47 years and ending only with her death, the second

to Starr and heading for a successful decade now. I was fortunate enough that

both came my way, giving me those good people I so much needed to find the

marital success I’ve enjoyed.

In the case of my writing, I had to go

looking.

When I started out with my writing

career, I was living in East Palo Alto on the San Francisco Peninsula. I rented

a water tower for $5 a month and wrote in there, concentrating on

science-fiction stories and doing Ki-Gor (a spin-off of Tarzan) novelettes for Jungle

Stories as John Peter Drummond, where I truly learned plotting. But I

wanted to break into the so-called slick market with more general fiction, for

not only the money, but also to have my work read in large-circulation magazines

such as Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s, American, and

other such periodicals then in business.

I’d learned that the most successful

freelancers working on the Peninsula then were Samuel W. Taylor, who’d written

everything from Saturday Evening Post serials to short stories to novels

to nonfiction books to movies, and his friend Rutherford Montgomery, one of the

most successful juvenile authors ever to come along that literary path. I also

learned that Sam was president of the local Authors Guild which met in San

Francisco. I joined the Authors Guild and met Sam. And when I learned that Sam

was driving Monty to the next meeting as a guest speaker, I suddenly developed

car trouble. I phoned Sam and asked if he could drive me to that meeting too.

The night of the meeting I found myself

riding in the back seat of an automobile containing Sam and Monty up front. How

surrounded by successful people can you get? I rode, listening, and learned more

about the writing business I was trying to enter from those two pros conversing

than I’d learned in my entire prior life.

I had interested a literary agent about

then and sent him several short stories pointed at that larger general market.

He’d tried to sell some without success. The two I’d most recently sent he

returned without trying to sell them, writing that they weren’t good enough

even to put on the market. I told Sam about that. He said, "Let’s see

them." He read the stories and said, "The hell they aren’t. Send

them to my agent and I’ll write him an introduction for you."

I sent them to his agent who sold one

to American and the other to Collier’s.

Now I had the agent. Now I could start

writing that first novel. Opportunistic? Well, maybe. But not at anyone’s

expense. And how much do you want to be a writer anyway? It’s how much I

wanted to be one.

Now I had the agent. Now I could start

writing that first novel. Opportunistic? Well, maybe. But not at anyone’s

expense. And how much do you want to be a writer anyway? It’s how much I

wanted to be one.

The new agent was Carl Brandt, of

Brandt & Brandt. He had writers ranging from Sinclair Lewis to John P.

Marquand. And it was about now when I saw on one of those hour-long TV dramas so

popular then a young highly gifted actor playing the part of a character named

Buggie, a hip musician-type and the personification of evil. I wrote down the

actor’s name when the credits rolled. And then the plot of my first novel

began shaping itself around a pivotal character named, you guessed it, Buggie.

I tried the idea with Carl Brandt, who

said, "Write it." To finance it, I got a job as an expediter in an

electronics plant and started writing the book evenings. When it was completed,

I sent it to Carl who gave it to his book agent, Lucille Baumgarten, who thought

it would work best in paper and sold it immediately to Dell. I quit my job,

determined to use the advance money so carefully that I could write full time.

Meantime, although I didn’t know it, Carl and his son, Carl, Jr., sent a copy

of the book to Cosmopolitan. Days later they sold the first serial rights

to that magazine for twice what the advance had been from Dell. Publication of

the Cosmo version preceded the Dell.

Just days after the Cosmo sale,

Marty and I were awakened by the telephone. I got up and answered it. In those

days, telegrams were popular. A Western Union clerk read this one to me. I went

back to bed and Marty said, "What was that?"

"A telegram."

"What kind of telegram?"

"An invitation to a party."

"What kind of party?"

"A Hollywood party."

"Who’s throwing it?"

"Saturday Evening Post. It’s

for all those movie stars they’ve profiled. I don’t know anybody at the Post."

"Where’s the party going to

be?"

"At the Beverly Hilton Hotel in

Beverly Hills next weekend. It’s RSVP. I’ll send them a telegram we’re not

going."

"What do you mean we’re not

going!"

"We can’t afford it!"

"What the hell do you mean we can’t

afford it! You made more on your book these past days than you did all year

working in that electronics plant! Get on the phone! RSVP them we’re coming!

And wire for hotel reservations too!"

"What hotel?"

"The Beverly Hilton Hotel, you

idiot!"

The stars at that party included the

brightest of the era, including John Wayne, Zsa Zsa Gabor, Jayne Mansfield and

Charlton Heston. Carl Brandt had wrangled my invitation from his brother who was

on the staff of the Post. Carl’s personal reward to me for writing that

novel.

There’s an addendum. A few years

later I was in Los Angeles pushing a new book. I told Jay Richards, my Hollywood

agent then, about how, in my first novel, I’d patterned Buggie after the young

actor I’d seen on TV.

"Who was the young actor?"

Jay asked.

"Mark Rydell. I sent him a copy of

that first book and explained his influence."

"He’s a director now, for Gunsmoke.

I’ll get his number. Phone him up. He’ll like hearing from you."

I wasn’t at all sure about that, but

I phoned. I said, "I’m sure you won’t remember me, but I’m Jim

McKimmey. And—"

"Jim! Where are you?"

"Here in Hollywood. And—"

"Let’s have lunch. Tomorrow

okay? Come over to the Desilu Studios and ask for me. About one? And bring your

new book. I want to read it."

We had lunch in the commisary at Desilu

the next day, the Hollywod party all over again, only more so. I never admired

Mark Rydell more, before or after that lunch, no matter how that gifted

gentleman later ascended as one of the most important directors of our day.

That’s how it happened, selling that

first book.

AG: Now that’s what I call an answer! Thanks, Jim. Before I ask you

about some of the other good people you surrounded yourself with (among them

John D. MacDonald and Ray Bradbury), I want to backtrack to a question about

the Ki-Gor novelettes you wrote for Jungle Stories. This is news to

me. How many did you write and over what period of time? Were they based on your

own ideas or did you write them to order from outlines? And have you used

any other pseudonyms apart from John Peter Drummond?

JM: I don’t remember how many Ki-Gor

novelettes I wrote for Jungle Stories. Only two or three within a year’s

span, I think. Malcolm Reiss, a great editor with Fiction House, had bought some

of my science fiction for Planet and asked me if I’d like to do some

Ki-Gors. It was income and experience, and I went for it.

I read Hemingway’s African adventures

as well as Robert Ruark’s. I think I got the flora-fauna down okay. I plotted

them well enough, I think, and they were my own ideas. But I couldn’t make the

characters talk right. Malcolm Reiss wrote me and said he liked everything but

the dialogue. Malcolm said that Ki-Gor, a product of the jungle, talked a lot

like a British aristocrat, which was a bit disconcerting.

I stopped writing them when I sold my

first slick short story.

As far as pseudonyms, I also used

Turkel Jones. Another was Benjamin Swift, and how that came about was that Joe

Gores, one of the few really good writing friends in my life, told me about a

guy who was making a good living writing novels designed to assist slow school

readers. The guy was Albert Nussbaum, who’d once been on the top ten list of

the most wanted criminals in America. He’d been doing time at Leavenworth, had

corresponded with Joe about writing from that prison, and had gotten out because

Joe Gores stood up at a hearing and convinced a board that Al should be

released.

I wrote to Al, who lived in Los

Angeles, and introduced myself. In turn, Al gave me the name of his editor at

Scholastic which resulted in my selling that publisher Buckaroo. Al also

introduced me to Pitman to whom I sold Play-Off, which was published

under the Benjamin Swift pseudonym.

After Al found out I’d been selling

to Good Housekeeping, I tried to return his favors by suggesting that we

collaborate on a short story for the late, great GH fiction editor, Naome

Lewis. We decided to use a pseudonym, of course. I can’t remember it now –

it was something like Mary Truestuff or something similar. We put

"HEART" in the title because they liked heart in titles. And we worked

out a story, back and forth, and came to a polished product which Al mailed from

L.A. under that pseudonym. Back came a wonderful letter from Naome Lewis. We

didn’t sell it, but it was close. The last I heard from Al, who later died,

was a letter written on a cruise boat where he was a guest writer along with

none other than John D. MacDonald.

AG: After the sale of The Perfect Victim in 1958 you suddenly had

the freedom to write full time. How hard did you find it to structure your time?

Your output was extremely impressive. By my calculations you’d had ten novels

published by the end of 1963! Did you put in your six or seven hours a day come

rain or shine, or did you write in bursts? What was your secret?

JM: I tried to put in six or seven

hours a day. But I didn’t always do it. And sometimes I put in more hours than

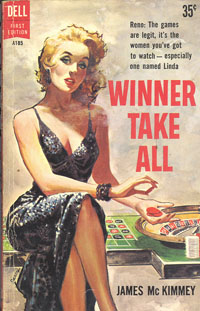

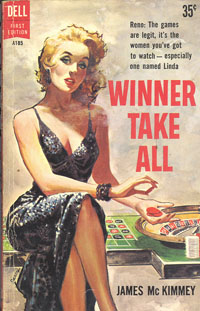

that. An example would be Winner Take All. I got the idea I could write

5,000 words a day. So I sat down with that goal in mind. And I did it for 10

days in a row, no matter what the hours added up to. That’s how long it took

to write Winner, 10 days, 50,000 words. I read it through once and edited

it that much. I then asked Marty, my wife then, if she would type it onto bond.

I didn’t want to look at it again. She did. It sold immediately. Anthony

Boucher gave it a fine review. I wrote The Satyr next and completed that

one in 17 days. But I could never do those two things again.

JM: I tried to put in six or seven

hours a day. But I didn’t always do it. And sometimes I put in more hours than

that. An example would be Winner Take All. I got the idea I could write

5,000 words a day. So I sat down with that goal in mind. And I did it for 10

days in a row, no matter what the hours added up to. That’s how long it took

to write Winner, 10 days, 50,000 words. I read it through once and edited

it that much. I then asked Marty, my wife then, if she would type it onto bond.

I didn’t want to look at it again. She did. It sold immediately. Anthony

Boucher gave it a fine review. I wrote The Satyr next and completed that

one in 17 days. But I could never do those two things again.

I think the real and only secret

involved in writing and selling at any sort of prolific rate is having an

actively buying market for your product. During that interval to which you’re

referring, there was still a good paperback original market. But as in all

aspects of life, conditions changed. Dell stopped publishing the kind of books I’d

been writing. In fact, by that time, they’d bought The Hot Fire and

didn’t publish it within the usual time frame they had those before it. Later,

they decided to publish the book. And, because of the good contract my agent had

drawn up, they had to buy it from me all over again.

It’s quite simple, really. Any writer

has got to have a market for his wares. I suppose if a writer is good enough,

there’s usually a market somewhere for what he or she has written. But I think

it’s possible that there are some really fine manuscripts out there that aren’t

published simply because there’s no good market for them. Time can change

that, of course. But if it takes too much time, how long can any writer live?

AG: You don’t write detective novels, focussing

instead on the viewpoint of the ordinary man, the victim, and, often, the

criminal - on many occasions pre-dating the contemporary thriller by using

multiple viewpoints in the same novel. What was it that drew you towards this

particular (and, to my mind, fascinating) branch of crime/mystery writing?

JM: When I began writing The Perfect

Victim, I didn’t think that I was writing anything in the crime/mystery

genre. I just had this basic idea and overall plan for a novel. When I’d

finished, I realized that the book could be in that general category. There was

a murder, after all. After it sold to Dell and then to Cosmopolitan, I

knew the effort was definitely in the crime/mystery arena. So I didn’t go

there on purpose, I just naturally happened to get there.

Where the multiple viewpoints came from

I definitely remember. During that phase when I was writing for Fiction House,

which is to say Planet and Jungle Stories, my editor was the

legendary Malcolm Reis. He was a marvel. It was for him that I started writing

the longer-length stories. I was using a single viewpoint and I was having

trouble. Malcolm wrote me a letter of advice that has remained with me to this

moment. He said, "Think in terms of your longer stories being movies. Move

that camera around so that you’re getting different points of view." I

began to think in those terms and was astonished to find that it made all the

difference for me. And it was primarily using that technique in my novel-writing

that produced whatever that branch of crime/mystery writing most of my books

might represent.

AG: Which of your Dell novels generated the most

income for you? Deservedly so? Was there any talk of movie adaptations?

JM: The Dell novel that generated the

most income for me was the first one, The Perfect Victim. It did so

because it also was sold to Cosmopolitan, had good foreign sales and also

was optioned twice as a movie. The first option was to Stanley Frazen who also

optioned one of John D. MacDonald’s books. As John wrote to me at the time,

"I hope you realize that we are now in a most curious relationship. If the

movie Frazen is making from Soft Touch, which for some reason which

passeth all understanding they have retitled Deadlock, makes any money

for Frazen, then he will very probably pick up your option." Frazen didn’t

pick up the option. But the book was again optioned when Paramount story editors

Joe Goldberg and John Boswell optioned all of my paperbacks for films. Although

that option was renewed, none of the books were made into a movie.

The longer efforts that generated the

most income were the short novels, or novellas, I wrote for Good Housekeeping,

a Hearst publication like Cosmo. There were only three as I recall – a

new editor-in-chief replaced the original novellas with second-rights condensed

romance novels, which obviated the opportunity to do more of them. You

understand that the dollar was worth more then. My price was in five figures.

And so we could live a year on one sale of one novella to GH. Add a short

story here and there, and we could live very comfortably. We had a big

camper-truck at the time, and I would go out daily somewhere in these Sierra

mountains, usually by a beautiful stream, and write so many words of one of

those novellas. The reward, over and beyond the doing and the monetary reward,

was eventually seeing the work in a magazine with about five million readers. It

was the time of any commercial writer’s life and surely the time of mine.

If there was a personal favorite of any

of those longer efforts, I guess it was The Perfect Victim. I liked that

story, and it opened up so much for me.

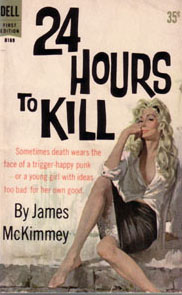

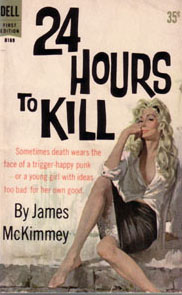

AG: You mentioned John D. MacDonald again, and I promised I’d ask you to

elaborate. Among other things, the John D. MacDonald quote ("This man

[McKimmey] can manipulate tension and character in ways that are beginning to

alarm me") that appears on the back cover of your novel, 24 Hours To

Kill, inspired me to write an article (James McKimmey: the Man Who

Alarmed John D. MacDonald) on the way you build tension in Run If You’re

Guilty. Just how much of an influence was he?

JM: The MacDonald influence has been, I

guess, rather huge. But I would also like to include Ray Bradbury in this answer

because, dissimilar as they were, both were very big writing heroes to me. Both

gave me a tremendous amount of time, attention and encouragement. Both became

extraordinarily successful. Ray is still the hero to me he always was. I was

enormously impressed by his work. I still am. But that has been a different

influence than John’s. Ray writes on pure instinct. He taught me to rely on

that much more than I might have otherwise. But most of us just can’t approach

writing exactly as Ray does for the simple reason that he, in my opinion, is a

genius. What he has done, and how he has done it, is not what the rest of us can

do. I believe that Ray has a very good concept of who he is as a writer and what

he has accomplished. But I don’t think that he truly recognizes the fact that

he is genius. Which, all by itself, makes him one of the nicest geniuses who has

ever come down the literary trail. That’s what I think about Ray Bradbury.

JM: The MacDonald influence has been, I

guess, rather huge. But I would also like to include Ray Bradbury in this answer

because, dissimilar as they were, both were very big writing heroes to me. Both

gave me a tremendous amount of time, attention and encouragement. Both became

extraordinarily successful. Ray is still the hero to me he always was. I was

enormously impressed by his work. I still am. But that has been a different

influence than John’s. Ray writes on pure instinct. He taught me to rely on

that much more than I might have otherwise. But most of us just can’t approach

writing exactly as Ray does for the simple reason that he, in my opinion, is a

genius. What he has done, and how he has done it, is not what the rest of us can

do. I believe that Ray has a very good concept of who he is as a writer and what

he has accomplished. But I don’t think that he truly recognizes the fact that

he is genius. Which, all by itself, makes him one of the nicest geniuses who has

ever come down the literary trail. That’s what I think about Ray Bradbury.

John MacDonald, on the other hand, was

a highly industrious man with very good intelligence, who could think his way

along his career with great good judgment and taught himself to write as well as

he did by writing. And I could better relate to that in terms of trying to do

likewise. Early in my career, the late, great mystery critic and science-fiction

editor, Anthony Boucher, rejected one of my short stories with the notation that

I was writing as good Bradbury fiction as Bradbury wrote on a bad day. I had to

take stock.

Then came my interest in John D.. The

same Anthony Boucher later reviewed one of my Dell novels, the one with

MacDonald’s quote, stating that I was using the ways (my emphasis) of

MacDonald by then, but not aping the style as I had that of Ray Bradbury. I got

over attempting to write exactly like Mr. Bradbury, but I don’t think I ever

quite got over using the ways of Mr. Macdonald, which is to say that I wanted to

write entertaining fiction with as much sense of place as existed in reality, do

it for as many readers as possible and get paid as much as I could for doing it.

I never remotely approached John’s readership or, certainly, his earnings. But

the desire to do it was always there.

And there is where heroes and followers

part ways. The hero does it. The follower only tries to do it. One cannot

successfully imitate genius. Which is why there is only one Ray Bradbury. But

can you successfully, and truly, imitate a writer such as John D. MacDonald? I

don’t think so. I don’t believe he was a genius. But he had a combination of

qualities including a desire and ability to work harder than anyone else in the

world that made him the unique writer he became. Most of us don’t want to work

as hard as he did as a way of professional life. I didn’t. But if I had, I

still wouldn’t have accomplished precisely what he did because his traits as a

writer were unique to him.

I see nothing wrong whatever in having

heroes. They can give you what you need when you need it. But eventually certain

of their capabilities entirely outweigh yours. What happens then is that you

start depending more and more upon your own capabilities, those unique to you.

That’s when you become the entity that is honestly what you are.

But those earlier heroes leave their

marks so that what you eventually become includes a part of what they were. I

was very fortunate to have had two men such as John D. MacDonald and Ray

Bradbury as the principal heroes of my life. Whatever qualities I might have as

a writer, as opposed to the deficiencies, which I definitely own as well, those

two surely helped develop. I’ve been extraordinarily lucky to have had them in

my life.

AG: The short story is a form you have mastered. For a period in the ‘50s

every issue of If included one of your science fiction stories. Similarly

in the ‘70s, Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine boasts a huge number

of your crime stories. You’ve placed just shy of four hundred short stories in

your career, and there are plenty more to come. How does your approach to

writing the short story differ from that of writing a novel?

JM:

If you love to write

you ain’t doing it right;

but if you love to have written,

being a pro’s where you’re gittin’

Having presented that, I hope I’ve

made two indisputable impressions. (1) I shall never be a poet. (2) Writing is

the hardest work in this world, and so the great satisfaction is having done it.

Short stories, of course, usually

provide a far quicker return for the effort than does writing the novel, one

major reason I seem to have preferred writing them.

A perfect example is one entitled Last

Reunion. I woke up at home on the ranch south of San Francisco and realized

that I wanted to write a short story but didn’t have an idea in my head. I got

in the car and went searching for one. I drove west to the ocean. By noon I

found a rustic seafood restaurant built right next to the water. During lunch I

was inventing a former WWII infantry captain, down on his luck. Put a guy like

that in this restaurant by the sea. Etc., etc..

I drove home fast and started writing.

I wrote through dinner. I wrote through most of the night. When I got up late

the next day, I typed a final copy and sent it to my agent who sold it to Cosmopolitan

in three days. Cosmo published it within weeks. Days after it hit the

stands, my telephone rang.

It was a producer from an anthology TV

show, GE Theater. He’d like to buy my reunion story for the show. Did I have

an agent?

"Yes, sir!" I bellowed.

In the following months, I wrote a new

novel. We celebrated its completion by driving to Lake Tahoe for a few days of

well-earned rest. I’ve always been a celebrity fan. And this trip to Tahoe was

highlighted by sitting down in Harrah’s main casino lounge and finding

ourselves a few tables away from an easily recognizable Lee Marvin, with his

wife. I had admired this man for some time, a combat veteran of WWII, who’d

made it big as a realistic tough-guy actor. We smiled at him. He smiled back. If

ever a celebrity seemed open to being approached, it was Lee Marvin that day in

that cocktail lounge. We were the only four customers in there.

"I’d like to shake his

hand," I whispered.

"Go do it," Marty said.

"He was a Marine sniper during the

war."

"He’d be pleased to know that

you know that."

"If I went over, he’d probably

ask us to join them."

"Did you have better plans?"

"That was a joke!"

"Go ahead. Do it."

But I’d read how much celebrities

hated being approached when they were relaxing. And at the rate Mr. Marvin was

putting down drinks, I knew he was relaxing a whole lot. I couldn’t finally

bring myself to interrupt his pleasure.

A few months later, in a TV listing, I

learned that Last Reunion was being shown the following Sunday night.

There was no other information in those days, including who would be starring.

You’ve guessed it? Isn’t that

marvelous?

Wasn’t it marvelous, to sit and watch

my story right there on that television screen starring none other than Lee

Marvin. That’s what a short story can do for you. Of course, that was the only

short story that did quite that much for me. But the history of it rings of the

sort of glitter and glamour and personal reward that I love. Perhaps if any of

the options on my novels had been exercised, I’d feel differently. But that’s

how it has personally been.

My only faint regret is that I didn’t

know that Lee Marvin, when we’d been sitting a table away from him, had been

the star of my dramatized short story – they’d obviously filmed the show

before we both arrived at Tahoe.

Yeah, it would have been fun,

especially if he’d indeed have invited us to his table. But I’ll happily

settle for the way it all happened, with that short story, any day, any week.

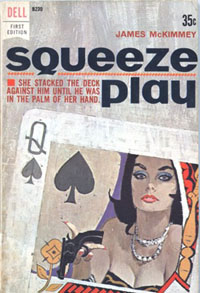

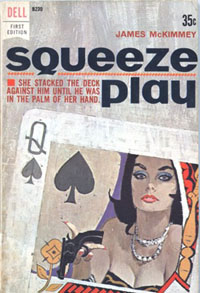

AG: You write fondly about nature and gambling (see Run If You’re

Guilty and Squeeze Play for excellent examples). You write about

small town America with ambivalence (The Perfect Victim through to The

Man With The Gloved Hand). Are these fair comments?

JM: Although I’ve never been a true

outdoorsman, I’ve always loved the outdoors. When I was in the Army in

Georgia, I found myself in the country on a field trip (with my military

buddies, of course) lying on the ground in my bedroll as a cold January rain

poured down on us. And then when I was in Normandy, on the way to combat in

Germany, it was outdoors in the rain again except we were able to share two-men

pup tents for shelter. And I swore I would never again camp out, and I never

have since.

But I have enjoyed long walks in the

kind of country in which I now live and hope I’ve reported it with some

accuracy in my work.

Gambling has long fascinated me. I

recognize the fact that it can be as deadly to some as booze is to others, but

it’s there. And I’ve lived in a gambling community for 42 years, so I think

I know a lot about it. I have no doubt that it was Ernest Hemingway’s

involvement in it that attracted me in the first place. I don’t glamorize it

anymore. But I still get a kick out of walking through a casino. By now,

however, it’s a rare day indeed when I find myself in a casino.

Gambling has long fascinated me. I

recognize the fact that it can be as deadly to some as booze is to others, but

it’s there. And I’ve lived in a gambling community for 42 years, so I think

I know a lot about it. I have no doubt that it was Ernest Hemingway’s

involvement in it that attracted me in the first place. I don’t glamorize it

anymore. But I still get a kick out of walking through a casino. By now,

however, it’s a rare day indeed when I find myself in a casino.

Ambivalence is right, about my attitude

toward small towns. I spent until age 13 living in small towns in Nebraska. Then

I found myself in Omaha. Omaha is not a city in the sense of New York City, of

course. But it’s a city. And I loved being there from the day I arrived. I

haven’t been back for a very long time, but I still have the very best

memories of that city. The small towns, however, have limitations that I simply

do not like. I don’t like being watched, the way they watch you in small

towns. I don’t like the community spirit necessary for existence in such

towns. I don’t like the limited vision that comes with small-town existence.

South Lake Tahoe is, of course, a relatively small community. But because of the

gambling, because of the world-class resort nature of a very beautiful mountain

town, drawing visitors from everywhere else in the world, the basic nature of

this place is extremely cosmopolitan. The result is the best of both the small

town and the city. I’ve liked

living here.

Your comments were fair indeed.

AG: We’ve spoken about your crime novels, mentioned your short fiction,

and a little while back Buckeroo slipped in almost unnoticed. Would you

care to tell us more about your science fiction short stories, and your literary

and remedial-reading novels?

JM: I got into science fiction because

of Ray Bradbury’s influence. I found some buying markets, such as Planet

and If. But I never got into it in the fashion of, say, Philip K. Dick.

Phil and I corresponded a lot when we were both starting out. I saved his

letters, and he had no idea that he would become a sort of icon in the

science-fiction world. He was just writing what he felt he had to write, and

perhaps there’s a lesson there.

I wrote a couple of remedial-reading

novels, Buckaroo and Play-Off as well as some short stories. But I’m

such a simple writer that it was no trouble for editors to turn the work into

fiction geared for high school students reading at a fourth-grade level. Several

of my adult stories landed in the same textbook anthologies.

I really never wrote much with a

deliberate intent of achieving literary quality. I think when I really enjoyed

writing a short story, and sold it to a target market, was when I later had it

picked up in what might be called a literary anthology. An example was a story

entitled The Man Who Danced. I wrote that for and sold it to Alfred

Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine. Then it was picked up for a college-level

text book entitled Literature 1 which also featured short stories written

by all of those writers I’d studied in college, from Steinbeck to Hemingway. I’ve

always been proud of that inclusion.

Part

Two of the interview continues here

Allan Guthrie: In 1957 Cosmopolitan published a shortened version

of your first novel under the title Riot At Willow Creek. In 1958 Dell

published the longer version as The Perfect Victim. How on earth did you

manage to sell a first book so successfully?

Allan Guthrie: In 1957 Cosmopolitan published a shortened version

of your first novel under the title Riot At Willow Creek. In 1958 Dell

published the longer version as The Perfect Victim. How on earth did you

manage to sell a first book so successfully? Now I had the agent. Now I could start

writing that first novel. Opportunistic? Well, maybe. But not at anyone’s

expense. And how much do you want to be a writer anyway? It’s how much I

wanted to be one.

Now I had the agent. Now I could start

writing that first novel. Opportunistic? Well, maybe. But not at anyone’s

expense. And how much do you want to be a writer anyway? It’s how much I

wanted to be one. JM: I tried to put in six or seven

hours a day. But I didn’t always do it. And sometimes I put in more hours than

that. An example would be Winner Take All. I got the idea I could write

5,000 words a day. So I sat down with that goal in mind. And I did it for 10

days in a row, no matter what the hours added up to. That’s how long it took

to write Winner, 10 days, 50,000 words. I read it through once and edited

it that much. I then asked Marty, my wife then, if she would type it onto bond.

I didn’t want to look at it again. She did. It sold immediately. Anthony

Boucher gave it a fine review. I wrote The Satyr next and completed that

one in 17 days. But I could never do those two things again.

JM: I tried to put in six or seven

hours a day. But I didn’t always do it. And sometimes I put in more hours than

that. An example would be Winner Take All. I got the idea I could write

5,000 words a day. So I sat down with that goal in mind. And I did it for 10

days in a row, no matter what the hours added up to. That’s how long it took

to write Winner, 10 days, 50,000 words. I read it through once and edited

it that much. I then asked Marty, my wife then, if she would type it onto bond.

I didn’t want to look at it again. She did. It sold immediately. Anthony

Boucher gave it a fine review. I wrote The Satyr next and completed that

one in 17 days. But I could never do those two things again. JM: The MacDonald influence has been, I

guess, rather huge. But I would also like to include Ray Bradbury in this answer

because, dissimilar as they were, both were very big writing heroes to me. Both

gave me a tremendous amount of time, attention and encouragement. Both became

extraordinarily successful. Ray is still the hero to me he always was. I was

enormously impressed by his work. I still am. But that has been a different

influence than John’s. Ray writes on pure instinct. He taught me to rely on

that much more than I might have otherwise. But most of us just can’t approach

writing exactly as Ray does for the simple reason that he, in my opinion, is a

genius. What he has done, and how he has done it, is not what the rest of us can

do. I believe that Ray has a very good concept of who he is as a writer and what

he has accomplished. But I don’t think that he truly recognizes the fact that

he is genius. Which, all by itself, makes him one of the nicest geniuses who has

ever come down the literary trail. That’s what I think about Ray Bradbury.

JM: The MacDonald influence has been, I

guess, rather huge. But I would also like to include Ray Bradbury in this answer

because, dissimilar as they were, both were very big writing heroes to me. Both

gave me a tremendous amount of time, attention and encouragement. Both became

extraordinarily successful. Ray is still the hero to me he always was. I was

enormously impressed by his work. I still am. But that has been a different

influence than John’s. Ray writes on pure instinct. He taught me to rely on

that much more than I might have otherwise. But most of us just can’t approach

writing exactly as Ray does for the simple reason that he, in my opinion, is a

genius. What he has done, and how he has done it, is not what the rest of us can

do. I believe that Ray has a very good concept of who he is as a writer and what

he has accomplished. But I don’t think that he truly recognizes the fact that

he is genius. Which, all by itself, makes him one of the nicest geniuses who has

ever come down the literary trail. That’s what I think about Ray Bradbury. Gambling has long fascinated me. I

recognize the fact that it can be as deadly to some as booze is to others, but

it’s there. And I’ve lived in a gambling community for 42 years, so I think

I know a lot about it. I have no doubt that it was Ernest Hemingway’s

involvement in it that attracted me in the first place. I don’t glamorize it

anymore. But I still get a kick out of walking through a casino. By now,

however, it’s a rare day indeed when I find myself in a casino.

Gambling has long fascinated me. I

recognize the fact that it can be as deadly to some as booze is to others, but

it’s there. And I’ve lived in a gambling community for 42 years, so I think

I know a lot about it. I have no doubt that it was Ernest Hemingway’s

involvement in it that attracted me in the first place. I don’t glamorize it

anymore. But I still get a kick out of walking through a casino. By now,

however, it’s a rare day indeed when I find myself in a casino.