Allan Guthrie's interview with James McKimmey (pictured) continues...

AG: You mentioned WWII a while back. Did you see

combat? If it’s not too painful, I’d love to hear about it.

JM:

I did see combat in Germany during World War II. I was in the 102nd Infantry

Division. But I was very lucky. I was in Headquarters Company of the 405th

Regiment, but not in the I & R platoon, which saw a lot of action. And in

time, because I’d had some college in my background and seemed a logical

choice to the captain of my company, I was sent back to Division Headquarters as

an assistant clerk. So we were always well behind those forward rifle companies.

For what action I was involved in I did receive two campaign battle stars, the

Combat Infantryman Badge and the Bronze Star. I don’t believe I earned any of

those medals nearly as much as so many of my compadres did, back then. But you

notice that I list all of them, which is what happens when you reach 80. You

tend to glorify as time goes on.

JM:

I did see combat in Germany during World War II. I was in the 102nd Infantry

Division. But I was very lucky. I was in Headquarters Company of the 405th

Regiment, but not in the I & R platoon, which saw a lot of action. And in

time, because I’d had some college in my background and seemed a logical

choice to the captain of my company, I was sent back to Division Headquarters as

an assistant clerk. So we were always well behind those forward rifle companies.

For what action I was involved in I did receive two campaign battle stars, the

Combat Infantryman Badge and the Bronze Star. I don’t believe I earned any of

those medals nearly as much as so many of my compadres did, back then. But you

notice that I list all of them, which is what happens when you reach 80. You

tend to glorify as time goes on.

But I don’t mean to say that I

glorify war in any manner. These days I often hear people who have never been

near battle shout that we should immediately go to war to solve an international

situation and shout that anybody who disagrees with them is a traitor. So, in

effect, they are accusing me of being a traitor, and my response to that is to

say, simply enough – stick it.

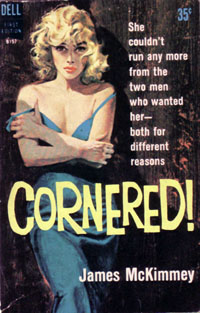

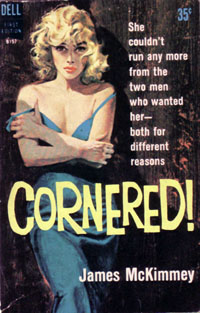

AG: Tell ‘em, Jim. Back to your crime novels. I’m going to pick out

(after much agonising), one or two that stand out for me. Cornered (Dell,

1960), Squeeze Play (Dell, 1962) and Run If You’re Guilty

(Lippencott, 1963) are three of the best crime novels written in the Sixties.

What are your memories of writing them? Do you remember how they were received

(both critically and commercially) at the time? And when did you last read them?

JM:

Oddly, I don’t remember very much about the reception and the writing of

either Cornered or Squeeze Play. I do remember how it went with Run

If You’re Guilty because it was my first hardcover. I always sent two

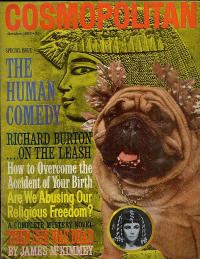

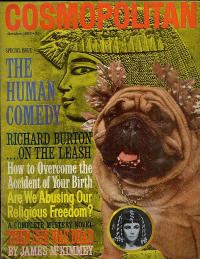

copies of chapters and outline of a projected novel to my agent. One went to Cosmopolitan

for a go-ahead on the eventual sale of first U.S. serial rights, the other

package went to the book publisher, which had usually been Dell, for paperback

publication. I got a go-ahead from Cosmo. But this time my agent tried a

hardcover house, Lippincott, for the books rights. He got a contract there, and

I got a letter from the Lippincott editor who’d bought it.

JM:

Oddly, I don’t remember very much about the reception and the writing of

either Cornered or Squeeze Play. I do remember how it went with Run

If You’re Guilty because it was my first hardcover. I always sent two

copies of chapters and outline of a projected novel to my agent. One went to Cosmopolitan

for a go-ahead on the eventual sale of first U.S. serial rights, the other

package went to the book publisher, which had usually been Dell, for paperback

publication. I got a go-ahead from Cosmo. But this time my agent tried a

hardcover house, Lippincott, for the books rights. He got a contract there, and

I got a letter from the Lippincott editor who’d bought it.

The letter was entirely patronizing,

telling me that because I knew only how to write paperbacks, she would, as I

completed the book, guide me along the path to successful hardcover publication.

Here again came some John D. MacDonald influence in that he believed without a

fraction of doubt that a book was a book was a book, no matter hard or soft

cover. I had come to the same belief. So, being relatively young and

feeling I was beginning to own the world of book-writing and not yet hewing to

the rule of putting away smoking letters to be reviewed in the calm of the next

day, I fired off a letter to the Lippincott editor.

I told her (a) that my paperbacks had

gotten three times what she was paying for this book and (b) that Cosmo

was getting the serial rights for five times what she was paying and (c)

paperback publication in the past had been my choice, not the result of an

inability to write for hardcover publication.

Of course, it was a rude, arrogant,

nasty letter I never should have written to an old long-established hardcover

mystery editor. But her attitude did represent much of the editorial view of

paperbacks at that time. Nevertheless, the contract had already been signed and

so Lippincott obviously published the final version of the completed novel. But

my agent told me that the editor there promised him that she would never buy

another book from me. She didn’t.

For you now, Al, to tell me that this

book is one of three of the best crime novels written in the Sixties puts a

special joy in my heart. And I thank you for that.

I hadn’t read any of these books for

perhaps at least 40 years. But because of your interest, I read Squeeze Play

a few weeks ago. I’m reading Cornered. I’ll read Run If You’re

Guilty after that.

AG: I’m interested in how it felt to read Squeeze Play after all

that time? Also, on the subject of editors, how much editorial input did Dell

have?

JM: How it felt to read Squeeze Play

was as though someone else had written the novel. And, of course, that’s true.

When you were forty years younger, you were a different man. And the way that

man forty years younger than I wrote when he wrote Squeeze Play was an

interesting discovery.

This older man found faults, of course,

mentally rewriting this or that as I read. But basically I was pleased with what

I found, in a book written by this younger man. One of my praises for any piece

of writing is that it’s professionally written. And to my surprise and

pleasure, I found Squeeze Play to be that, both in construction and

word-handling. That probably sounds very egotistical, but I’m not saying it

out of ego. I tried to analyze my reaction and it goes this way:

When I wrote Squeeze Play, I’d

been writing for about 13 years. When I was attending the University of San

Francisco, I wrote a column for the college’s newspaper, The Foghorn,

and I also wrote a column for the San Mateo Times. In addition, while I

was still in college, I’d started writing and publishing short fiction. I

continued writing short stories after college. And then, before I set out on Squeeze

Play, I’d written and had published six other crime novels, along with a

trail of rejections slips for other things that had not succeeded to signal my

course for exactly what it had been – writing and failing and succeeding and

writing and failing and succeeding, on and on in that fashion.

And along with that had been a lot of

study about how other writers had done it. I studied those other writers’

work. I read everything I could find written by those same writers about how

they’d done what they had done.

And I think, there, is the inherent

value of Noir Originals – spotlighting writers in the fashion you’re

spotlighting Jason Starr and me. Right now I’m reading your coverage of Jason.

We don’t write in the same style. We don’t work in the same way. We have

enormously different backgrounds. I’m from a small town in Nebraska. Jason is

a born New Yorker. We produce entirely different products, albeit in the same

overall category of Noir.

But what I did and what Jason did too,

was study, study, study. What we also did was write, write, write. And what both

of us did as well was fail, fail, fail. Out of all of that has come whatever

success we’ve individually had. If learning about how it went for us can help

other, newer writers out there, then Noir Originals is worth its weight in

literary gold.

On the subject of editors, I had a

great deal of revising requested on the first novel Dell bought, The Perfect

Victim. After that, there was less and less of it from Dell as I wrote

succeeding books. There was no input from Cosmo. But what was

difficult there was cutting the length of the books by more than half. That wasn’t

involved, of course, in two stories Cosmo published as novels, And

Then She Was Dead and Kill Him Again because they were written

directly for Cosmo at that magazine’s length

AG: The Cosmo version of Run If You’re Guilty was called Death

Trap. Was that a deliberate homage to John D. MacDonald’s 1957 novel of

the same name?

JM:

It wasn’t a deliberate homage to John D. I wouldn’t have done that. The

problem is that I don’t remember whose title that was, although Cosmo

used more of my titles than anyone else. I don’t believe Dell used a single

one of my titles. I think it was Cornered that I originally called The

Red Snow. For quite some time I saved every letter I got from an editor, and

I saved every copy of the letters I wrote to them. But with the years and moving

from place to place, all of that has gone the way of so many things out of one’s

past. Just the other day I was looking in a mirror, trying to find some small

hint of what was there fifty years ago. I couldn’t find it.

JM:

It wasn’t a deliberate homage to John D. I wouldn’t have done that. The

problem is that I don’t remember whose title that was, although Cosmo

used more of my titles than anyone else. I don’t believe Dell used a single

one of my titles. I think it was Cornered that I originally called The

Red Snow. For quite some time I saved every letter I got from an editor, and

I saved every copy of the letters I wrote to them. But with the years and moving

from place to place, all of that has gone the way of so many things out of one’s

past. Just the other day I was looking in a mirror, trying to find some small

hint of what was there fifty years ago. I couldn’t find it.

AG: I think it was Peter Rabe who eventually

resorted to calling his Gold Medal novels by the name of the protagonist, since

Gold Medal repeatedly shunned his original titles. I wasn’t aware that Dell

did the same thing. Do you remember any of your other original titles?

JM: Riot At Willow Creek was my

original title for The Perfect Victim. That’s the only other one I

remember.

AG: While we’re still on the subject of Dell, what were the initial print

runs?

JM: 200,000.

AG: That’s a suitably impressive number. Moving on…

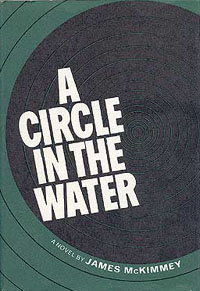

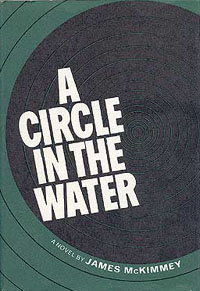

Blue Mascara Tears and A Circle In The Water are two

very different novels, both copyright 1965. They are, apparently, unconnected. A

Circle In The Water is not even a crime novel. However…

Inspector Jack Cummings (Blue Mascara Tears) is one of your most

compelling protagonists. And unusually (uniquely?), he’s a policeman. A

maverick, of course, obsessed with bringing a hood to justice. Cummings’

obsession borders on insanity. His initials (JC) are surely deliberate – as

are his comments on crucifixion. Otis Christenson (A Circle In The Water

- word for word perhaps your best work) is also a Christ figure (it’s no

coincidence that Christ is the first syllable of his surname).

What do you recall of these protagonists and the

novels they appear in?

JM: I can’t imagine a more perceptive

reader than you, Al. You’re finding things I’ve never considered. JC for

Jack Cummings for Jesus Christ. Christ the first syllable of Christenson. I

think it proves the theory that your subconscious can produce what is,

essentially, what you really mean.

I recall very clearly what I was trying

to do with the policeman, Jack Cummings. As a crime writer I’d naturally done

a lot of investigation into law officers. And I’d come to the conclusion that

quite often the difference between a talented law officer and a talented

criminal is a hairline. I don’t mean to indicate that I have the slightest

disrespect for law officers. I have the highest respect for them.

What I mean is that I strongly believe

that it’s the same kind of individual that can represent either law enforcer

or lawbreaker. How many people have got the guts to rob a bank? How many people

have got the guts to apprehend the bank robber? In the case of Jack Cummings,

his Godlike (or JC-like) attitude about bringing a hood to justice was what

separated him from being a hood himself. But in the end he crossed that line and

became a killer. I remember an old fiction rule that if you want to write

messages, use Western Union. But I suppose I was guilty in Blue Mascara Tears

of suggesting some sort of message about law enforcement. But again, I didn’t

do it with any disrespect for the law. Take away all law from any metropolis for

24 hours, and you would have hell on earth.

I

can’t analyze Otis Christenson as easily. A Circle In The Water was

simply an attempt to prove to myself that I could write a so-called serious

novel. Having started out to be an architect, having worked as a draftsman along

the way, I felt I could see through Otis’s eyes. But he was mainly a product

of that same subconscious. Writing that novel, I wasn’t restrained to some of

the rules that exist when you write the crime novel. Or at least that’s how I

felt then. I now feel very strongly that a suspense novel can be taken as

seriously as a serious novel if it is written well enough – Joe Gores and I

agree solidly on that.

I

can’t analyze Otis Christenson as easily. A Circle In The Water was

simply an attempt to prove to myself that I could write a so-called serious

novel. Having started out to be an architect, having worked as a draftsman along

the way, I felt I could see through Otis’s eyes. But he was mainly a product

of that same subconscious. Writing that novel, I wasn’t restrained to some of

the rules that exist when you write the crime novel. Or at least that’s how I

felt then. I now feel very strongly that a suspense novel can be taken as

seriously as a serious novel if it is written well enough – Joe Gores and I

agree solidly on that.

Circle

was primarily my attempt then to prove that I could write that kind of novel. I

think a lot of us have had that desire. Philip Dick wanted all of his writing

life to prove that he was a "quality" writer, not just a

science-fiction writer. His science fiction sold well, his quality writing didn’t.

Well, take that "just a science-fiction writer" out of it. As it

turned out, he proved that all along he was a high-level quality writer who

happened to write science fiction.

I was glad I wrote A Circle In The

Water when I wrote it. But I had very little agreement about that at the

time. My agent tried very hard to discourage me from writing it. I wrote it

anyway and he sold it anyway. I was in Los Angeles when it was published.

William Morrow bought time on an L.A. television station that had a program

devoted to presenting new books. So I went on TV to promote the book. Afterward,

making phone calls from my hotel room, I discovered that there wasn’t a copy

of that book in any bookstore in the greater Los Angeles area. Now, Al, you are

saying that the book, word for word, is perhaps my best work. That means a great

deal to me. So thanks. And I’m still glad I wrote it!

AG: Promotion/publicity is a huge part of a contemporary writer’s job.

You mentioned making a television appearance to promote Circle. What was

generally expected of you to help market your novels back in the Sixties?

JM: You’re right that

promotion/publicity is huge part of a contemporary writer’s job. That wasn’t

the case in the Sixties. In that general time frame it was pretty much up to the

writer in most cases. Some used promotion extremely well. A classic example was

Helen Gurley Brown. She started her publicity blitz on that same Los Angeles TV

program I mentioned, developed a best seller and then became editor of Cosmopolitan.

While I was waiting to go on that L.A. show, I had a nice conversation with

Richard Armour, also a guest that day. He was probably the most popular poet of

the era, and he did a lot of self-promotion, so that as a poet he was well

known.

In science-fiction, the conventions

served well as promotions. I remember getting Christmas cards from Poul and

Karen Anderson relating their travels during the previous years, as Poul, a

highly popular s-f writer, was a featured convention speaker around the world.

Bradbury did a lot of that.

I did a little, speaking to high-school

classes and such things as that. I even agreed to teach a couple of writing

classes at the local college. But I pulled my wife into it. She stood and

officiated, I sat and answered questions. I much preferred sitting down in front

of my typewriter and writing to standing up in front of an audience and

speaking. I recall one Northern California Regional Mystery Writers of America

meeting when I was living on the San Francisco Peninsula. I was pressed tightly

into a corner by Tony Boucher, Lee Offord and Miriam Allen DeFord and informed

that I was going to be the next Regional Vice President of that organization. It

was voted upon and passed.

In the following days, I thought about

standing up in front of that group at every monthly meeting to follow for the

next year. And I said to my wife, "We’ve been talking a lot about moving

up to Lake Tahoe, haven’t we?"

She said, "I guess so. Why?"

I said, "Let’s do it."

"When?"

"Right now."

So we did. And the MWA chapter found

someone else to officiate at the following meetings. I’ve lived here at Tahoe

ever since. I’ve really loved it. It’s been the only place for me. And so

for anyone to infer that the only reason I ever moved up here in the first place

was to get out of standing up and officiating at the monthly Northern California

Regional MWA meetings for a year is just downright silly.

It is, in fact, positively ridiculous.

You understand that, Al.

Don’t you?

AG: More than I’d care to admit, Jim. Hard to

believe, I know, but I’m actually pretty shy. Aside from John D. MacDonald,

which crime novelists (past or present) do you admire?

JM: Raymond Chandler was the first

novelist in this field to catch my interest. I discovered him at sea in the

year 1944. A large Swedish luxury liner had been converted to a troop carrier

during World War II. It was on this vessel, heading toward France, that I found

a paperback in the ship’s library written by Mr. Chandler. I would find a

place on our deck sit down and read what was a brand-new experience for me. I

loved what this writer was doing. I still remember reading a chapter or two and

then going up and watching the prow slice through the dark water of the North

Atlantic with high white spray flying out to either side, thinking about what I’d

read, and then returning to the book.

I think that kind of remained in my

subconscious as time went along. I read more Chandler. I read the writer who

reputedly influenced Chandler, Dashiell Hammett. I read Ross MacDonald, who was

reputedly influenced by Chandler. To bring it up to date, I read Joe Gores, who

I think is the best writer writing today.

I admire all of those.

But it was really music, jazz

specifically, that led me into writing. And I have my heroes there too.

I started playing the clarinet when I

was eleven years old. I played third chair, third clarinet in a band when I was

in Red Cloud, Nebraska, and I also played in a clarinet quartet that went to a

regional music contest and scored a "Good," with the judges. After

moving to Omaha and attending Omaha Central High School, I played in the band

and, when I was a senior, again went to one of those regional music contests. By

this time I was in a clarinet quartet that got a "Highly Superior" at

the music contest, and I was playing first chair first clarinet in the band. I

rented a saxophone and tried to play two or three dance gigs in town.

But the fact was that I wasn’t

naturally good as a musician; it was simply that I practised a lot. I was far

too shy to be an effective soloist even if I had been a better musician.

So I didn’t become an architect as my

original intended profession. I didn’t become a jazz musician either. I became

a writer because that’s what I could naturally do best.

But it was the love of music that

created the most influence on my writing. I knew you had to practice in order to

improve as a writer. So I did a lot of that, writing for newspapers, smaller

magazines, anything. It was something that came out of the musical experience

– if you want to create a great jazz solo on the piano, you’d better learn

how to play the piano. Going back to Joe Gores, what he did to be a writer after

he’d graduated from Notre Dame was follow an instructor’s advice, locked

himself up in a room, and wrote, wrote, wrote, the kind of woodshedding that led

him into being the successful writer he is today.

Music remains my strong influence right

down to today. I’ve had the fortune to be able to meet and talk to some of the

best jazz musicians ever to live, Count Basie, Johnny Hodges, Eddie

"Lockjaw" Davis. I would still like to improve my writing style so

that it would more nearly match the deceptive simplicity of Count Basie’s

piano. I would still like to have the superb tone of Johnny Hodges’ alto

saxophone. I would still like to have the driving force of Lockjaw’s tenor

saxophone.

Years ago I would have been hesitant to

reveal the above comparisons for public consumption. I was afraid that it might

sound a bit weird. But then I heard an acceptance speech delivered by one of

this globe’s very best actors, Jack Nicholson, when he accepted one of his

Oscars. Among others, he thanked Miles Davis for his success. For non-jazz

readers, Miles Davis, a trumpeter, composer and all-round innovator, represented

one of the largest talents ever to participate in the jazz world. Making

absolutely no other comparisons to the monster talent owned by Mr. Nicholson, I

think I understand what he meant by thanking Miles. It was the trumpet sound

Miles developed, I’m certain, and it was also how Miles developed not only his

individual sound, but the sound of the jazz groups he led, gotten by studying

artistic accomplishments outside the jazz world such as the writing of Jean-Paul

Sartre or the dancing of the Ballet Africaine.

I’ve hardly pretended to such lofty

artistic heights as that. But I still find myself thinking in musical terms when

it comes to writing. In these latter years, I’ve been collaborating with my

wife, Starr, who did her woodshedding as a newspaper journalist and writing a

nonfiction book recently published. One of those collaborations is a short story

appearing in this issue of Noir Originals. We’ve written nonfiction pieces

that have been published. We wrote a play that has not yet been produced but,

from reactions so far received from some of best theatrical houses in the

country, it still has that potential. I’ve never found myself in a

collaboration that has worked, in the past. This time it’s working. It’s not

only the talent of Starr, which is heavy. It’s also the way I’m viewing it

now. In my head, we’re the same as a musical team. I write the first chorus.

Starr writes the second. Then we polish the entire melody to the final

manuscript, retaining the best of what each of us can contribute. And what we

get, hopefully, is a song worth hearing.

I’ve never before admitted this to

anyone. But you are, Al, getting me to talk at length and at great intimacy. I

should imagine, by now, that you’d highly welcome a one-sentence answer to one

of your questions.

I’ll try but I won’t promise.

AG: Okay,

Jim. Try answering this in one sentence! Two of your later novels, The Hot

Fire and The Man With The Gloved Hand are mysteries – not detective

novels, but ones in which the reader spends most of the book ignorant as to the

identity of the killer. Readers of those novels remain gripped as they try to

work out who was responsible for the murders. You were heading in this direction

with Run If You’re Guilty. This is a very different angle of approach

from the way you created tension in most of your earlier novels (The Wrong

Ones being a notable exception). In The Long Ride, for example, the

reader knows each character intimately. The tension in the novel exists in the

lack of information the various characters have about each other, and the

explosive events the reader anticipates when the characters reveal their true

purposes. Which goes to show that there’s no single way to create tension. As

a writer famous for manipulating tension, can you tell us how and where you’ve

achieved the best results?

AG: Okay,

Jim. Try answering this in one sentence! Two of your later novels, The Hot

Fire and The Man With The Gloved Hand are mysteries – not detective

novels, but ones in which the reader spends most of the book ignorant as to the

identity of the killer. Readers of those novels remain gripped as they try to

work out who was responsible for the murders. You were heading in this direction

with Run If You’re Guilty. This is a very different angle of approach

from the way you created tension in most of your earlier novels (The Wrong

Ones being a notable exception). In The Long Ride, for example, the

reader knows each character intimately. The tension in the novel exists in the

lack of information the various characters have about each other, and the

explosive events the reader anticipates when the characters reveal their true

purposes. Which goes to show that there’s no single way to create tension. As

a writer famous for manipulating tension, can you tell us how and where you’ve

achieved the best results?

JM: As I stated early in this

interview, I wasn’t really aware that I was writing anything in the

crime/mystery genre. I just kind of slipped into it. As I said, ‘I didn’t go

there on purpose, I just naturally happened to get there.’ Now, this many

questions later, I realize that what I said then reminds me of an old jazz

story. This young fellow with a trumpet asked for a job with a dance band and

was asked if he’d had any formal training on his instrument. His answer:

"Not enough to hurt nothing."

I’m not foolishly proud that I didn’t

know more about writing mysteries than I did when I was starting out. It was

just that I had majored in American literature in college. I wrote my final

thesis on William Saroyan. And I just wasn’t as much influenced by a really

good whodunnit as I was by The Daring Young Man On The Flying Trapeze,

although I realize now that you would have a hard time detecting that any of my

early novels had been influenced by that famous piece of literature. But when I

was attending college in San Francisco, I even tracked down where Mr. Saroyan

lived and, although I never had the privilege of meeting him, I used to drive

past his house and think, "Someday, by God, I would like to go and do

likewise."

Well, Saroyan, like Bradbury, is not to

be successfully imitated. I’m just trying to say that I became more and more

aware of the mystery genre as I wrote it and read it, with the consequent result

that I think I was trying harder to obtain a better mystery than simply

presenting a good story. And so, looking back, I think now that the best results

in what I was trying to do were achieved with the earlier novels simply because

they were composed more naturally for my particular bent as a writer. Having

finally reread both Squeeze Play and The Man With The Gloved Hand,

I definitely feel that Squeeze Play is the better book.

I don’t know. Well, okay. Suppose

your final question reduces to this: Did

you study the mystery story before you began writing it?

I suppose my answer would have to be,

"Not enough to hurt nothing."

AG: Thanks, Jim. I’d love to carry on talking

to you, but, sadly, we’re going to have to wrap this up. Here’s my final

question: In a career spanning more than fifty years, what have been your high

points?

JM: 1: I was a junior at the University

of San Francisco. One of my classes was creative writing taught by a lay

instructor. Another was Shakespeare taught by a Jesuit priest who was also the

head of the English Department.

An assignment for the creative-writing

class was to write a short story.

And so I went home and wrote my first

short story which I entitled The Greatest Modern Author In The World, which,

of course, was what I intended to be. The main character was a fellow to whom I

gave the wonderful name of Miniver Cheevy. In the story, it was Miniver who

wanted to be that greatest modern author, but the poor fellow couldn’t find

anything to write about. I sent him past great story situations, one after

another, and he never saw the possibilities. At the end, he still knew that one

day he would be that greatest author if only he ever ran across a good idea. It

was satire, of course. I turned the story in to the instructor, certain that I’d

written a good short story.

Grading was on the ABC system. I got

the story back with a C minus.

C minus for a first short story is a

high point in a career?

Don’t touch that dial.

I’d found a "little"

magazine, The American Pen, that was going to publish a special issue

written by college students only. Payment would be copies of the issue. But it

would mean getting published. And so when I’d turned my short story in to the

creative-writing instructor, I’d also sent a copy to the magazine.

Hey! The magazine accepted the story. I

wanted to tell the instructor, but somehow I couldn’t. There’s a one-finger

salute quite popular today. If it had been then, I might have delivered that at

least.

But something even better happened. The

Jesuit teaching Shakespeare who was head of the English Department shook my hand

one morning and explained that he’d been sent a copy of the magazine

containing my story. He congratulated me profusely and said he’d given the

magazine to the creative-writing instructor, who never later mentioned it but

gave me nothing but A pluses for everything I turned in from that point forward.

2. Along the writing way, in the early Seventies, I was doing some nonfiction in

addition to the novels and short stories. And because I’d always loved

photography, I decided to add that to my creative efforts. I’d driven through

the Pocono Mountains of Pennsylvania earlier and tried a query about them with

both Good Housekeeping and Motorhome Life. I got an assignment

from both.

Hot damn, I went out and bought a bush

jacket, packed my camera gear, drove from my home in Lake Tahoe to Reno, got on

a United flight to New York City and checked into the Royalton Hotel on West

44th. The next morning I took a bus to Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania, rented a car

and photographed that area for most of the day. Took a bus back to Manhattan,

flew United back to Reno, drove home to Tahoe.

Look at me, a genuine

writer-photographer adventurer. I wrote articles for both magazines. Both were

purchased. Motorhome Life gave a full spread to my color photography. I

thought that it didn’t get better than that.

It happened once in my career. But it

happened.

3. Another fine time also involved New York City. I went there during an Edgar

week, also in the Seventies, when the Mystery Writers of America held their

annual awards banquet. I wasn’t nominated for anything, that year or any other

year, but it’s a time when writers and editors closely or remotely associated

with crime writing gather in Manhattan.

Again, I checked into the Royalton, The

Man With The Gloved Hand having just been completed. I started the week out

by having lunch with Bruce Cassiday, fiction editor of Argosy Magazine. I’d

been selling short stories to Bruce, now he wanted to hear about the new novel.

I thumbnailed it vocally, and he said, "We’ll buy the first serial

rights." Done. Sold. A nice way to start the week.

I next had lunch with Lee Wright, the

Random House mystery editor who’d bought the book version. Lee was a delight

and a hell of an editor, and she took me to one of the best restaurants in town

for that lunch.

Next was Ernie Hutter, editor of Alfred

Hitchcock Mystery Magazine. Ernie bought a lot of the kind of fiction I

truly liked writing. He’d arranged for a couple of other mystery writers who

appeared regularly in his magazine to join us, and we had a splendid lunch

together.

The Awards Dinner on a Friday night was

a glittery affair indeed. I sat at the Random House table. And somebody had

arranged for me to pick up the runner-up award for a writer who couldn’t

attend. The award was named, I was announced as the one picking up the award,

and all I had to do was stand up and go grab the damned scroll and listen to the

applause. I loved it. I didn’t mind that it wasn’t my scroll because in that

event I would have had to have given a speech to that large assembly.

The following day, I was invited to yet

another lunch, this one with Naome and Bob Lewis at their apartment at East 96th

Street. Naome was Fiction Editor at Good Housekeeping, Bob was a literary

agent and also a great jazz clarinetist who’d played with one of jazz’s

giants, Jack Teagarten. The Lewises had two of the most charming little girls

ever invented.

So there we were, having a drink, Naome

leaving now and then to check on lunch as her daughters made cookies just for

the visiting writer, me. Bob broke out his clarinet and delivered some of the

best sounds I’ve heard from that instrument. The food was great. Those little

girls stuffed cookies into my pockets as I was leaving so that I would have a

snack later on.

I flew back to Nevada the next morning,

exhausted and entirely happy with the whole experience.

4. There have been other high points in my career. But the one I’ve saved for

last is by far the very best of them all, this, what I’m doing with you, Al.

It is a rare and wonderful thing for

me, now, at age 80, to look back over all that represents what I’ve done as a

writer these past many years. And it’s a wonderful thing to know that not only

you but other writers, the younger ones, the new ones, the really good ones

writing the crime fiction of today, will be contributing to this coming issue of

your fine magazine.

I’m so delighted to have been chosen

by you for this recognition, so delighted to have become a friend of yours as

well as a friend of that wonderful wife of yours, Donna.

What you are doing counts most with me

over all of the good things that have come my way as a writer.

This, now, this minute, is when it

really doesn’t get better, with Starr beside me, my wife, the love of my life.

AG: Jim, I’m sure there are a few hardboiled souls shedding a few tears

right this minute. I don’t know which I’ve enjoyed more, reading your books

or talking to you. Both have been an absolute pleasure. On behalf of everyone

who has ever read a single word you’ve written, thank you.

JM:

I did see combat in Germany during World War II. I was in the 102nd Infantry

Division. But I was very lucky. I was in Headquarters Company of the 405th

Regiment, but not in the I & R platoon, which saw a lot of action. And in

time, because I’d had some college in my background and seemed a logical

choice to the captain of my company, I was sent back to Division Headquarters as

an assistant clerk. So we were always well behind those forward rifle companies.

For what action I was involved in I did receive two campaign battle stars, the

Combat Infantryman Badge and the Bronze Star. I don’t believe I earned any of

those medals nearly as much as so many of my compadres did, back then. But you

notice that I list all of them, which is what happens when you reach 80. You

tend to glorify as time goes on.

JM:

I did see combat in Germany during World War II. I was in the 102nd Infantry

Division. But I was very lucky. I was in Headquarters Company of the 405th

Regiment, but not in the I & R platoon, which saw a lot of action. And in

time, because I’d had some college in my background and seemed a logical

choice to the captain of my company, I was sent back to Division Headquarters as

an assistant clerk. So we were always well behind those forward rifle companies.

For what action I was involved in I did receive two campaign battle stars, the

Combat Infantryman Badge and the Bronze Star. I don’t believe I earned any of

those medals nearly as much as so many of my compadres did, back then. But you

notice that I list all of them, which is what happens when you reach 80. You

tend to glorify as time goes on. JM:

Oddly, I don’t remember very much about the reception and the writing of

either Cornered or Squeeze Play. I do remember how it went with Run

If You’re Guilty because it was my first hardcover. I always sent two

copies of chapters and outline of a projected novel to my agent. One went to Cosmopolitan

for a go-ahead on the eventual sale of first U.S. serial rights, the other

package went to the book publisher, which had usually been Dell, for paperback

publication. I got a go-ahead from Cosmo. But this time my agent tried a

hardcover house, Lippincott, for the books rights. He got a contract there, and

I got a letter from the Lippincott editor who’d bought it.

JM:

Oddly, I don’t remember very much about the reception and the writing of

either Cornered or Squeeze Play. I do remember how it went with Run

If You’re Guilty because it was my first hardcover. I always sent two

copies of chapters and outline of a projected novel to my agent. One went to Cosmopolitan

for a go-ahead on the eventual sale of first U.S. serial rights, the other

package went to the book publisher, which had usually been Dell, for paperback

publication. I got a go-ahead from Cosmo. But this time my agent tried a

hardcover house, Lippincott, for the books rights. He got a contract there, and

I got a letter from the Lippincott editor who’d bought it. JM:

It wasn’t a deliberate homage to John D. I wouldn’t have done that. The

problem is that I don’t remember whose title that was, although Cosmo

used more of my titles than anyone else. I don’t believe Dell used a single

one of my titles. I think it was Cornered that I originally called The

Red Snow. For quite some time I saved every letter I got from an editor, and

I saved every copy of the letters I wrote to them. But with the years and moving

from place to place, all of that has gone the way of so many things out of one’s

past. Just the other day I was looking in a mirror, trying to find some small

hint of what was there fifty years ago. I couldn’t find it.

JM:

It wasn’t a deliberate homage to John D. I wouldn’t have done that. The

problem is that I don’t remember whose title that was, although Cosmo

used more of my titles than anyone else. I don’t believe Dell used a single

one of my titles. I think it was Cornered that I originally called The

Red Snow. For quite some time I saved every letter I got from an editor, and

I saved every copy of the letters I wrote to them. But with the years and moving

from place to place, all of that has gone the way of so many things out of one’s

past. Just the other day I was looking in a mirror, trying to find some small

hint of what was there fifty years ago. I couldn’t find it. I

can’t analyze Otis Christenson as easily. A Circle In The Water was

simply an attempt to prove to myself that I could write a so-called serious

novel. Having started out to be an architect, having worked as a draftsman along

the way, I felt I could see through Otis’s eyes. But he was mainly a product

of that same subconscious. Writing that novel, I wasn’t restrained to some of

the rules that exist when you write the crime novel. Or at least that’s how I

felt then. I now feel very strongly that a suspense novel can be taken as

seriously as a serious novel if it is written well enough – Joe Gores and I

agree solidly on that.

I

can’t analyze Otis Christenson as easily. A Circle In The Water was

simply an attempt to prove to myself that I could write a so-called serious

novel. Having started out to be an architect, having worked as a draftsman along

the way, I felt I could see through Otis’s eyes. But he was mainly a product

of that same subconscious. Writing that novel, I wasn’t restrained to some of

the rules that exist when you write the crime novel. Or at least that’s how I

felt then. I now feel very strongly that a suspense novel can be taken as

seriously as a serious novel if it is written well enough – Joe Gores and I

agree solidly on that. AG: Okay,

Jim. Try answering this in one sentence! Two of your later novels, The Hot

Fire and The Man With The Gloved Hand are mysteries – not detective

novels, but ones in which the reader spends most of the book ignorant as to the

identity of the killer. Readers of those novels remain gripped as they try to

work out who was responsible for the murders. You were heading in this direction

with Run If You’re Guilty. This is a very different angle of approach

from the way you created tension in most of your earlier novels (The Wrong

Ones being a notable exception). In The Long Ride, for example, the

reader knows each character intimately. The tension in the novel exists in the

lack of information the various characters have about each other, and the

explosive events the reader anticipates when the characters reveal their true

purposes. Which goes to show that there’s no single way to create tension. As

a writer famous for manipulating tension, can you tell us how and where you’ve

achieved the best results?

AG: Okay,

Jim. Try answering this in one sentence! Two of your later novels, The Hot

Fire and The Man With The Gloved Hand are mysteries – not detective

novels, but ones in which the reader spends most of the book ignorant as to the

identity of the killer. Readers of those novels remain gripped as they try to

work out who was responsible for the murders. You were heading in this direction

with Run If You’re Guilty. This is a very different angle of approach

from the way you created tension in most of your earlier novels (The Wrong

Ones being a notable exception). In The Long Ride, for example, the

reader knows each character intimately. The tension in the novel exists in the

lack of information the various characters have about each other, and the

explosive events the reader anticipates when the characters reveal their true

purposes. Which goes to show that there’s no single way to create tension. As

a writer famous for manipulating tension, can you tell us how and where you’ve

achieved the best results?