Reviewed

by Lee Horsley

"And he was

certain, because he could feel it in the pit of his stomach, that they were

going to make it. Not a million bucks. Leave that to the fiction writers.

But a cool one hundred G’s, maybe. That was the kind of money it took the

average guy ten to twenty years of hard labor to earn. They could get it in

hours." (Squeeze Play, 39)

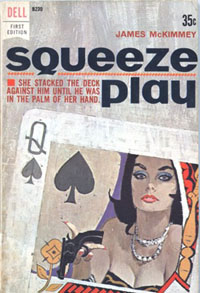

Much

of James McKimmey’s gripping, intricately plotted novel, Squeeze Play (Dell,

1962), is set in a Lake Tahoe casino, the scene of an elaborate, carefully

planned scheme to walk away safely with "a cool one hundred G’s". Squeeze

Play is a novel in which all of the main characters are – or ultimately

become – gamblers of one sort or another. Throughout, there is a dialogue

between "taking a chance" and fatalism, between game-playing and

passivity. The game-player or gambler is a familiar figure in mid-century

American crime writing. In the 1930s and 1940s, characters who rely on the roll

of the dice or the spin of the roulette wheel are generally (like the

protagonist of Richard Hallas’s You Play the Black and the Red Comes Up,

for example) committing themselves to a doomed enterprise. Their gambles signify

desperation; their games are played in the vain hope of breaking free from a

cycle of defeat and degradation.

Much

of James McKimmey’s gripping, intricately plotted novel, Squeeze Play (Dell,

1962), is set in a Lake Tahoe casino, the scene of an elaborate, carefully

planned scheme to walk away safely with "a cool one hundred G’s". Squeeze

Play is a novel in which all of the main characters are – or ultimately

become – gamblers of one sort or another. Throughout, there is a dialogue

between "taking a chance" and fatalism, between game-playing and

passivity. The game-player or gambler is a familiar figure in mid-century

American crime writing. In the 1930s and 1940s, characters who rely on the roll

of the dice or the spin of the roulette wheel are generally (like the

protagonist of Richard Hallas’s You Play the Black and the Red Comes Up,

for example) committing themselves to a doomed enterprise. Their gambles signify

desperation; their games are played in the vain hope of breaking free from a

cycle of defeat and degradation.

The world of Squeeze

Play is less grimly deterministic, partly because the powers-that-be are

less corrupt and less indiscriminately destructive than those that lurk behind

the scenes, controlling the course of events in much earlier literary noir.

Nevertheless, these established powers (though "straight") have in

place some very effective methods of surveillance, and the plans of the aspiring

crooks are very much shaped by the nature of this vigilance. The casino, a

"vast amphitheater of entertainment," has seemingly omniscient

observers ensconced behind an array of mirrored panels "on the ceiling

everywhere through the entire building, overlooking cash registers, crap tables,

roulette wheels, any place where money changed hands" (38; 42). McKimmey’s

schemers, however, see themselves as quite distinct from the compulsive gamblers

they intend to prey on, and as clever enough to evade the watchful eyes of both

police and casino owners. Suspense is heightened in the novel by the gradual

revelation of machinations that do actually seem to offer the criminals a chance

of success against this "legitimate house" and that threaten to bring

destruction on the protagonist, who becomes increasingly enmeshed in their trap.

"He awoke in the

strange room and stared at the ceiling, puzzled" (5): McKimmey’s central

character, Jack Wade, is seen in the first chapter literally waking up to the

danger he is in. By the end of the chapter he is running blindly, in the

position of one of the classic types of noir protagonist, the traumatised

"wrong man". With his sense of masculine competence and potency on the

verge of collapse, Jack is the victim of an accusation of double murder that he

finds incomprehensible. As the narrative shifts to the events of the preceding

eight days, and we begin to piece together the explanation of the situation he

is in, we share Jack’s conflicting emotions and our sympathies very much

remain with him. But McKimmey’s use of multiple viewpoints - of shifting close

third-person narration – ensures that readers are also given sharp insights

into the motives, the anxieties and weaknesses both of the conspirators and of

one of their other main victims, Binny, the wife of Jack Wade.

"He awoke in the

strange room and stared at the ceiling, puzzled" (5): McKimmey’s central

character, Jack Wade, is seen in the first chapter literally waking up to the

danger he is in. By the end of the chapter he is running blindly, in the

position of one of the classic types of noir protagonist, the traumatised

"wrong man". With his sense of masculine competence and potency on the

verge of collapse, Jack is the victim of an accusation of double murder that he

finds incomprehensible. As the narrative shifts to the events of the preceding

eight days, and we begin to piece together the explanation of the situation he

is in, we share Jack’s conflicting emotions and our sympathies very much

remain with him. But McKimmey’s use of multiple viewpoints - of shifting close

third-person narration – ensures that readers are also given sharp insights

into the motives, the anxieties and weaknesses both of the conspirators and of

one of their other main victims, Binny, the wife of Jack Wade.

For all of the main

characters in Squeeze Play, the inducement to become gamblers and

game-players is a sense of their own entrapment. The femme fatale (Elaine

Towne) and her chosen ally (Frank Delli, a dealer at the casino) are both

looking for a way out, battling against a humiliating conviction that their

lives have been wholly determined by the misfortunes of their earlier years.

Frank seems always to have had a sense of personal failure hanging over him. He

is a loser with a past he wants to leave behind – "he’d been on the

outside, a fumbler. He hadn’t been much good at anything he’d tried..."

(38). Frank’s feeling of inferiority and his terrible need to assert himself

are glimpsed, for example, in a scene juxtaposing his childish bravado with the

masculine competence of the sheriff. In contrast to the sheriff, who bags

mountain lions, Frank uses eight shots to blast away a tiger-striped domestic

cat that startles him, reflecting, "Somehow there was something about this

that was more complete, more definite, as though he had really done something,

shooting the hell out of that damn cat. . . ." (44-5) The self-confidence

of this chronically weak character increases under the tutelage of the

determinedly competent Elaine, to the point at which he feels equal to acts of

violence more serious than cat murder - even equal, perhaps, to committing his

own act of betrayal.

Elaine, driven by the

overwhelming urge to escape from a background of "cheap, patched-up

dresses" and a "shack-like house on the outskirts of town",

rejects a passive domestic role to pursue success in a game of her own choosing.

Convinced that sufficient will and ruthless intelligence will save her from the

fate of her mother, "an empty shell of a woman" whose main attachment

was to her husband and who was capable of nothing more than "a child’s

ability to meet life", Elaine clings to the belief that careful planning

can guarantee the success of her quest for "enough money for everything,

piles of it, heaped dollar upon dollar" (88-9). Everything depends upon her

meticulous plan, and she sees the game she sets up not as a gamble but as a sure

thing: both she and Frank feel "certain…that they [are] going to make

it." As the novel builds to a climax, though, we increasingly wonder

whether the foolproof plan may actually turn out to be more akin to a desperate

gamble, at the mercy of life’s sheer unpredictability, beset by human

instability, errors of judgement and the erratic behaviour of Elaine’s

co-conspirator.

Jack Wade and his wife

Binny, also struggling to reverse a fate that’s been monstrously unkind to

them, are not buoyed up by a conviction that they can seize control. Both,

following the death of their young son, feel at the mercy of life’s

randomness. Binny, a character of considerable pathos, is addicted to drink and

gambling, and obtains only temporary respite from her feeling of total

helplessness: "…the gambling…gave her more and more freedom, covered

the constant feeling of insufficiency, insecurity, and gave her the momentary

courage she could not live without" (49). Jack, on the other hand, strikes

us as temperamentally unsuited to gambling. Throughout most of the narrative, he

tries stoically to endure his ever more miserable lot – unhappily married,

downtrodden and persecuted at work – until danger makes him less risk averse,

finally driving him to become a player himself in a last-ditch effort to clear

his name. Too decent and acquiescent for his own good, Jack ultimately has to choose

to take a gamble. It is only by refusing to surrender passively to fate that he

stands any chance of avoiding the defeat that awaits most noir protagonists. As

he moves closer to making his own play, he increasingly speaks like a gambler

– "then we’ve got half a chance", "my best bet" –

until finally he is ready to act, "feeling a peculiar calm because he was

at last going to do something…" (168-9). Readers of Squeeze Play,

of course, can understand but not share Jack’s feeling of "peculiar

calm", since his decision carries us into the final scenes of a plot so

tense that we are compelled to read anxiously and rapidly to the end.

Copyright© 2004 Lee

Horsley

***

read

the opening chapter

read

some more!

read

An American Classic: Jason Starr's Pulp Originals Squeeze Play e-book

introduction

Purchase

Squeeze Play from Pulp Originals

After graduating from the University of

Minnesota, LEE HORSLEY

came to England as a Fulbright Scholar to do postgraduate work in English

Literature and has lived here ever since (with an English husband and three

children, now all in their twenties). She has been at the University of

Lancaster since 1974 - currently teaching twentieth-century British and American

literature and two specialist crime courses. Over the last fifteen years, she

has written two books on literature and politics – Political Fiction and

the Historical Imagination (Macmillan, 1990) and Fictions of Power in

English Literature 1900-1950 (Longman, 1995) – and more recently The

Noir Thriller (Palgrave, 2001). Her current projects include a book on

twentieth-century British and American crime fiction for OUP, supported by a

Research Leave Award (2003-04) from the AHRB; and another (jointly with her

daughter, Katharine) called Fatal Families: Representations of Domesticity

in Twentieth-Century Crime Stories (contracted to Greenwood Press). Both of

these should be out sometime in 2005-06. Together with Katharine, Lee is editor

and webmaster of Crimeculture. Lee is

also a co-editor and webmaster of Pulp Originals.

Contact Lee

Much

of James McKimmey’s gripping, intricately plotted novel, Squeeze Play (Dell,

1962), is set in a Lake Tahoe casino, the scene of an elaborate, carefully

planned scheme to walk away safely with "a cool one hundred G’s". Squeeze

Play is a novel in which all of the main characters are – or ultimately

become – gamblers of one sort or another. Throughout, there is a dialogue

between "taking a chance" and fatalism, between game-playing and

passivity. The game-player or gambler is a familiar figure in mid-century

American crime writing. In the 1930s and 1940s, characters who rely on the roll

of the dice or the spin of the roulette wheel are generally (like the

protagonist of Richard Hallas’s You Play the Black and the Red Comes Up,

for example) committing themselves to a doomed enterprise. Their gambles signify

desperation; their games are played in the vain hope of breaking free from a

cycle of defeat and degradation.

Much

of James McKimmey’s gripping, intricately plotted novel, Squeeze Play (Dell,

1962), is set in a Lake Tahoe casino, the scene of an elaborate, carefully

planned scheme to walk away safely with "a cool one hundred G’s". Squeeze

Play is a novel in which all of the main characters are – or ultimately

become – gamblers of one sort or another. Throughout, there is a dialogue

between "taking a chance" and fatalism, between game-playing and

passivity. The game-player or gambler is a familiar figure in mid-century

American crime writing. In the 1930s and 1940s, characters who rely on the roll

of the dice or the spin of the roulette wheel are generally (like the

protagonist of Richard Hallas’s You Play the Black and the Red Comes Up,

for example) committing themselves to a doomed enterprise. Their gambles signify

desperation; their games are played in the vain hope of breaking free from a

cycle of defeat and degradation.